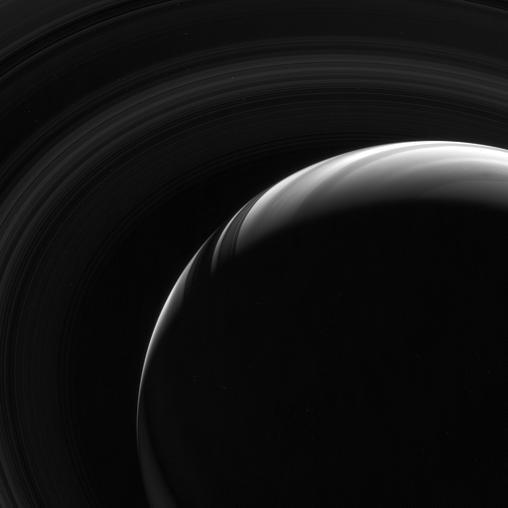

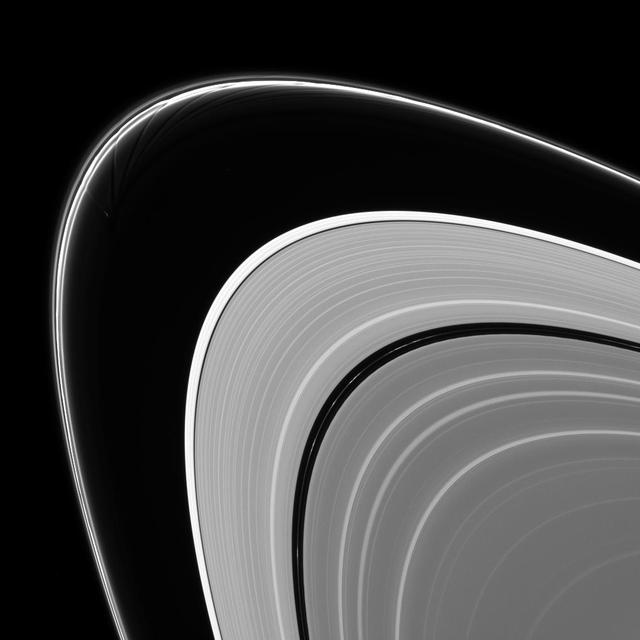

Near the Ringplane

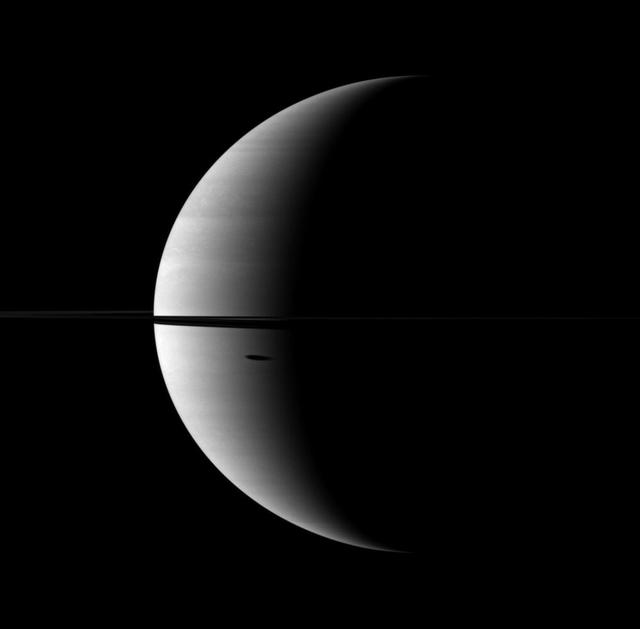

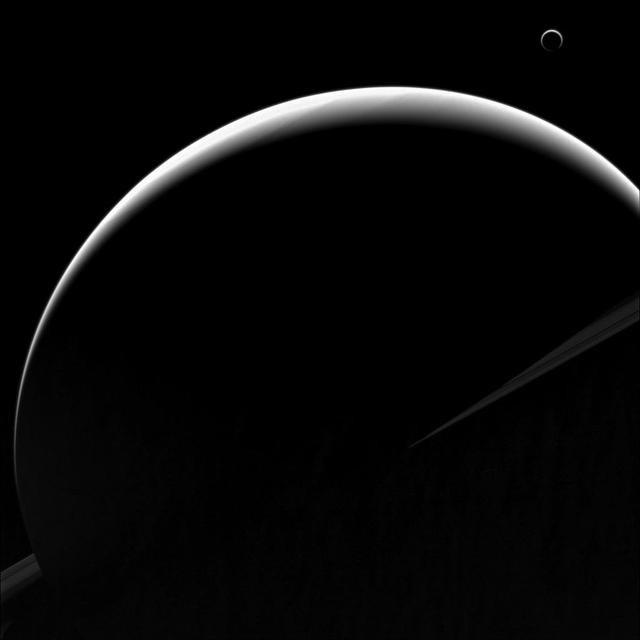

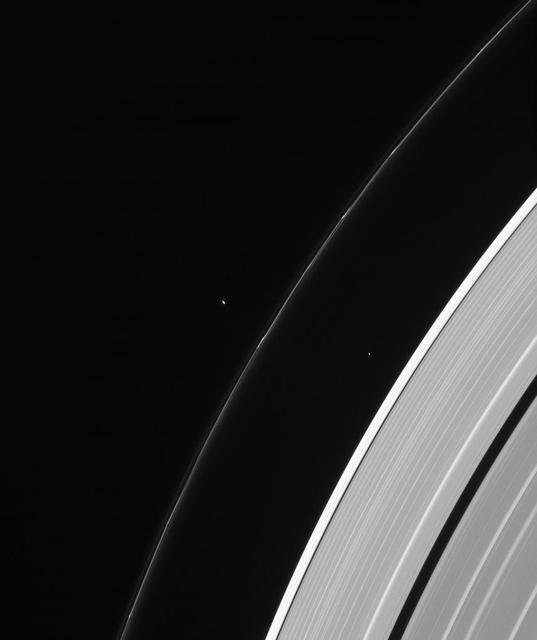

Night Side Ringplane

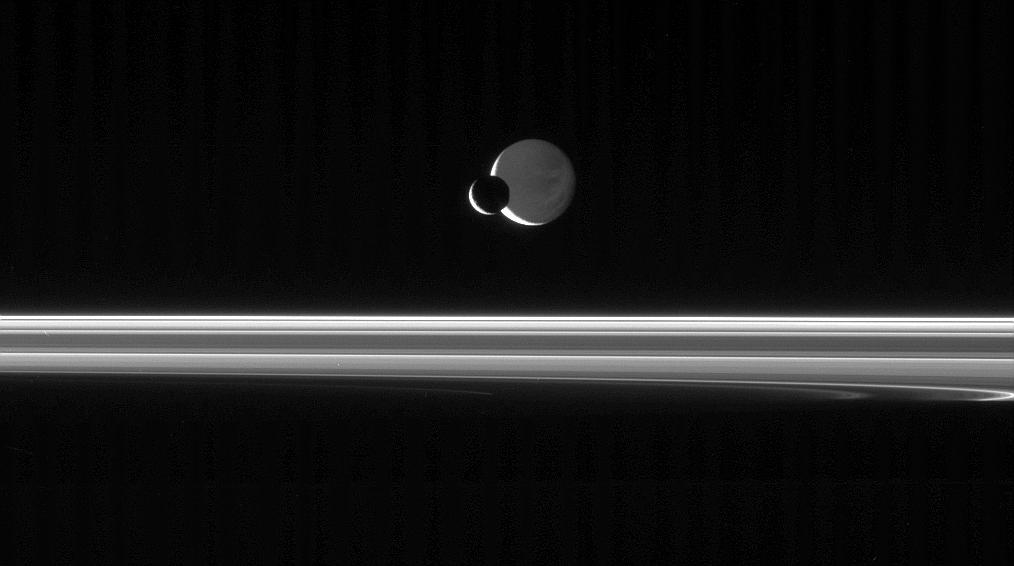

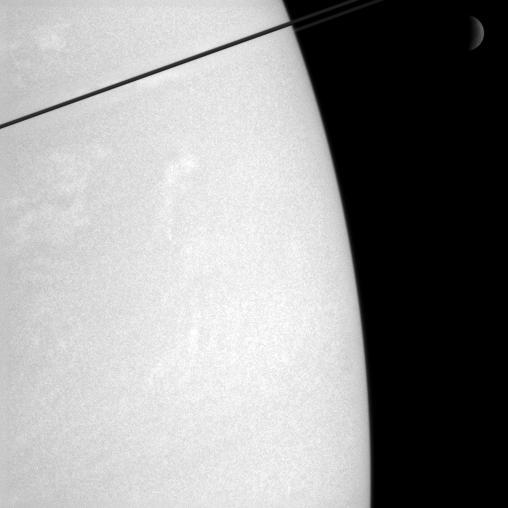

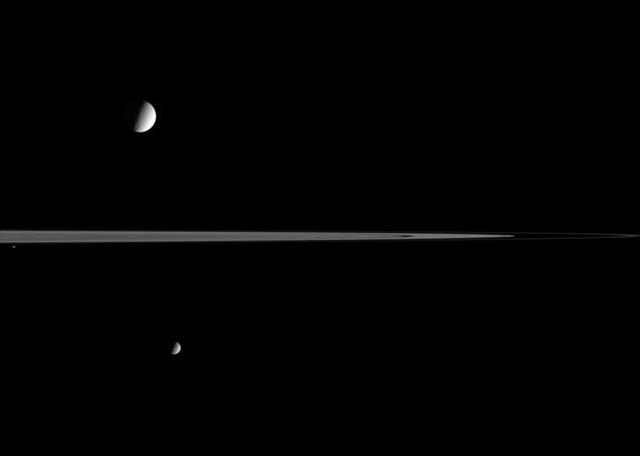

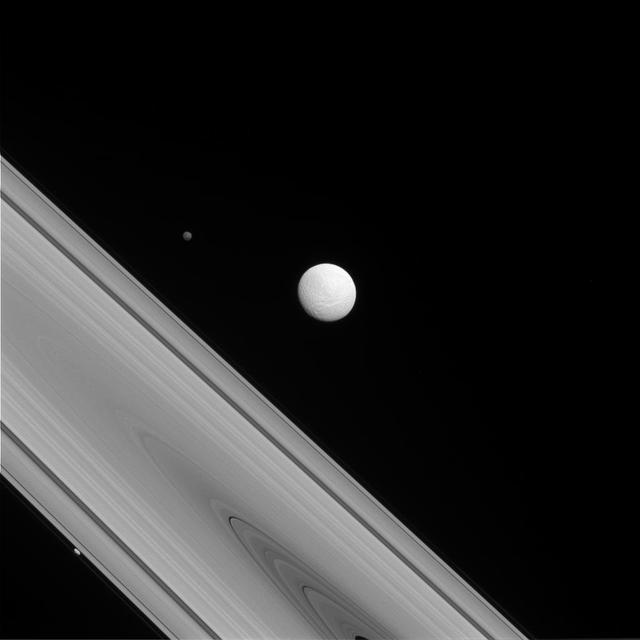

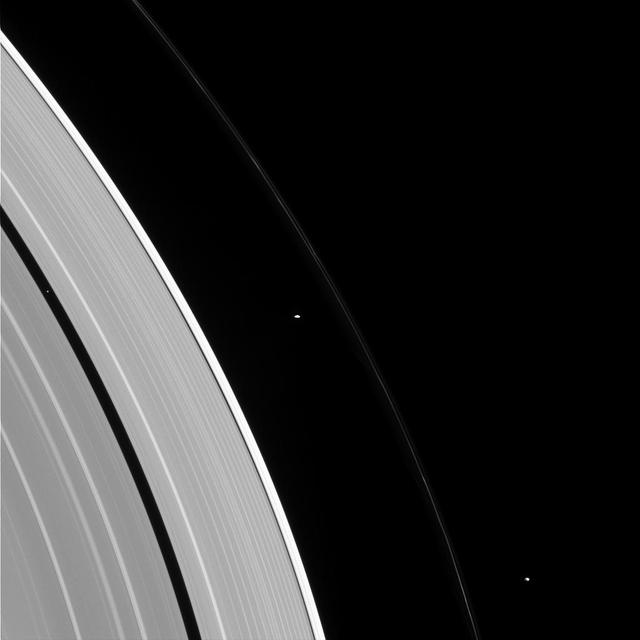

The Cassini spacecraft skims past Saturn ringplane at a low angle, spotting two ring moons on the far side

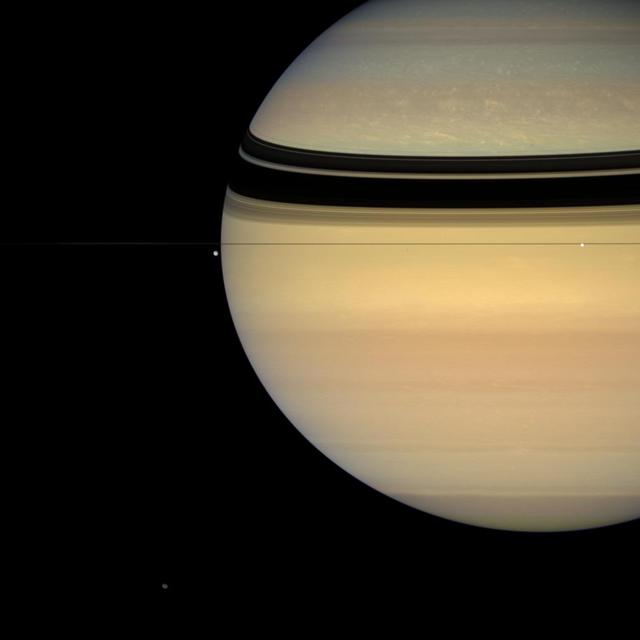

This colorful view, taken from edge-on with the ringplane, contains four of Saturn's attendant moons. Tethys (1,071 kilometers, 665 miles across) is seen against the black sky to the left of the gas giant's limb. Brilliant Enceladus (505 kilometers, 314 miles across) sits against the planet near right. Irregular Hyperion (280 kilometers, 174 miles across) is at the bottom of the image, near left. Much smaller Epimetheus (116 kilometers, 72 miles across) is a speck below the rings directly between Tethys and Enceladus. Epimetheus casts an equally tiny shadow onto the blue northern hemisphere, just above the thin shadow of the F ring. Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. The images were acquired with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 24, 2007 at a distance of approximately 2 million kilometers (1.2 million miles) from Saturn. Image scale is 116 kilometers (72 miles) per pixel on Saturn. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA08394

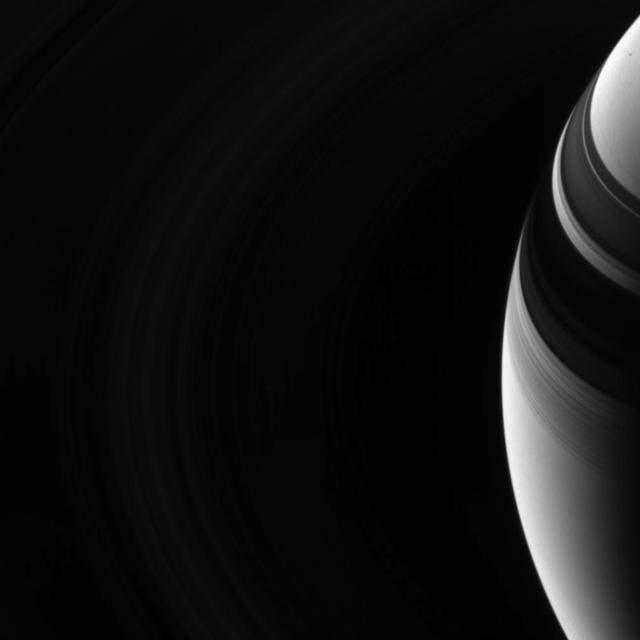

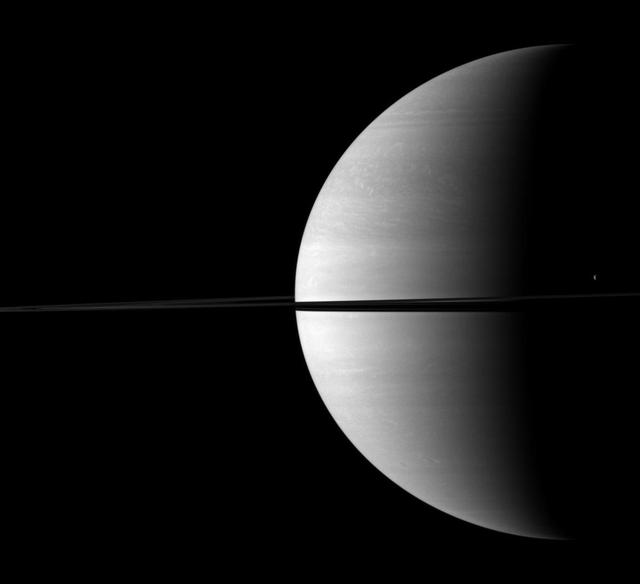

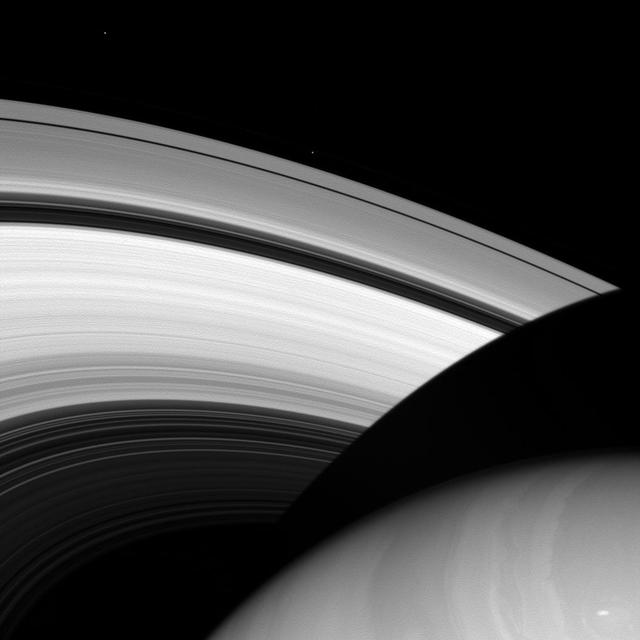

Saturn rings are dark and elusive in this view from high above the ringplane, but their shadows on the planet give them away

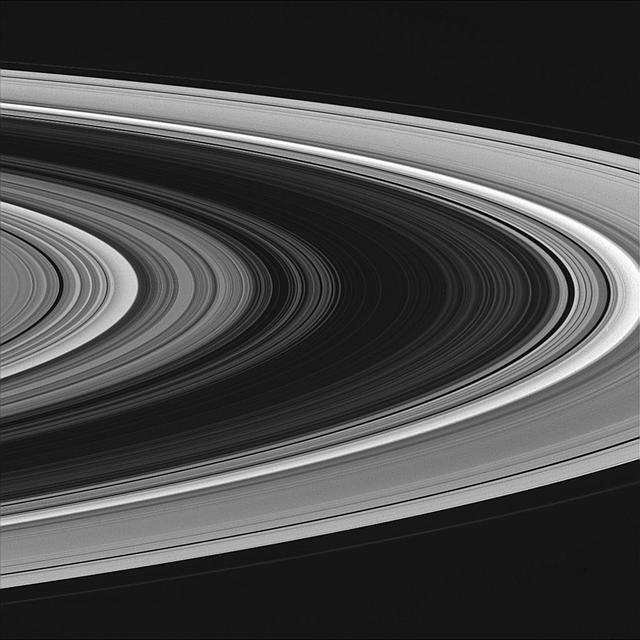

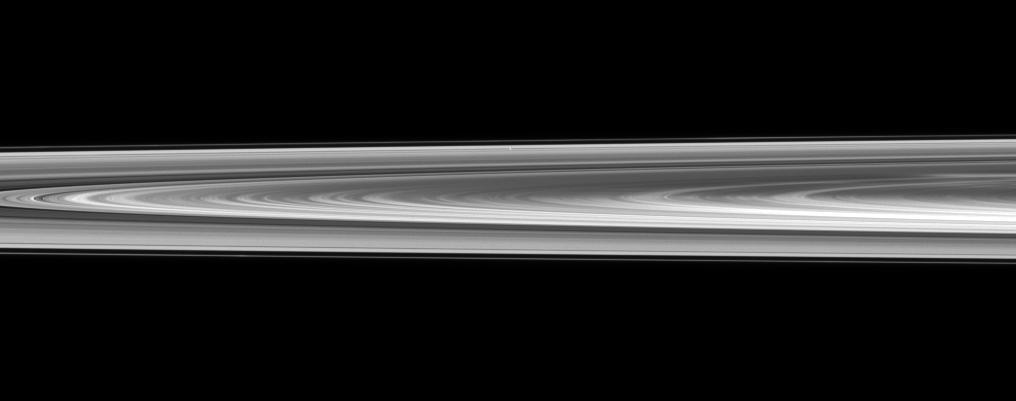

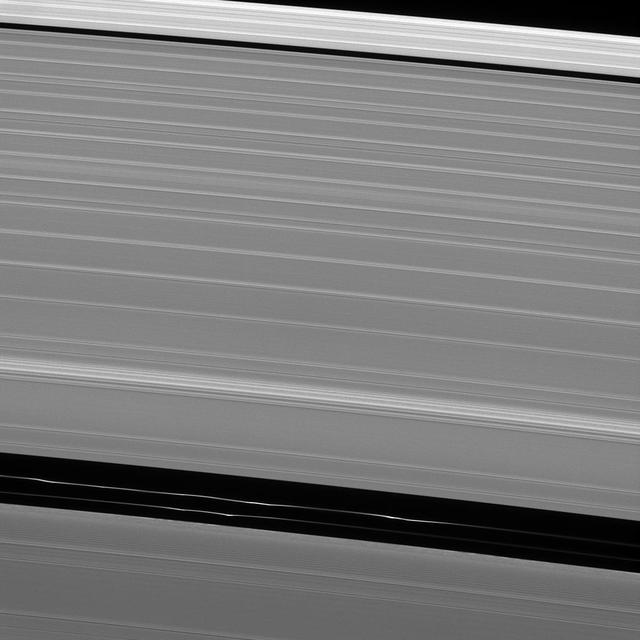

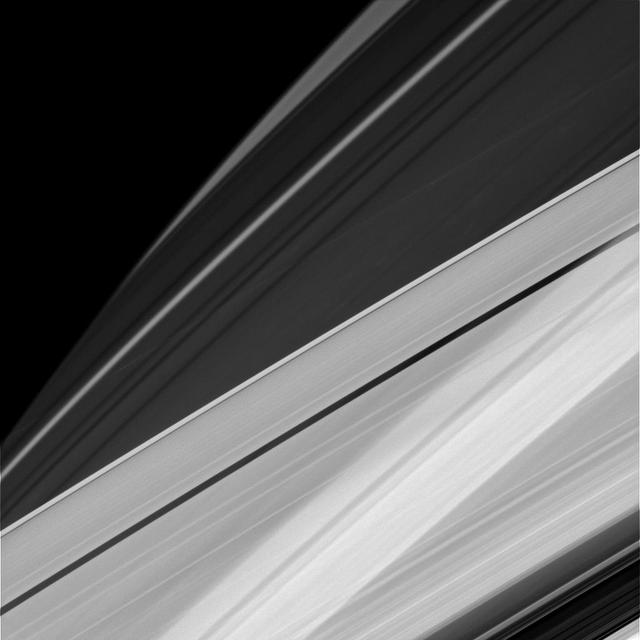

This group of spokes in Saturn B ring extends over more than 5,000 kilometers 3,100 miles radially across the ringplane

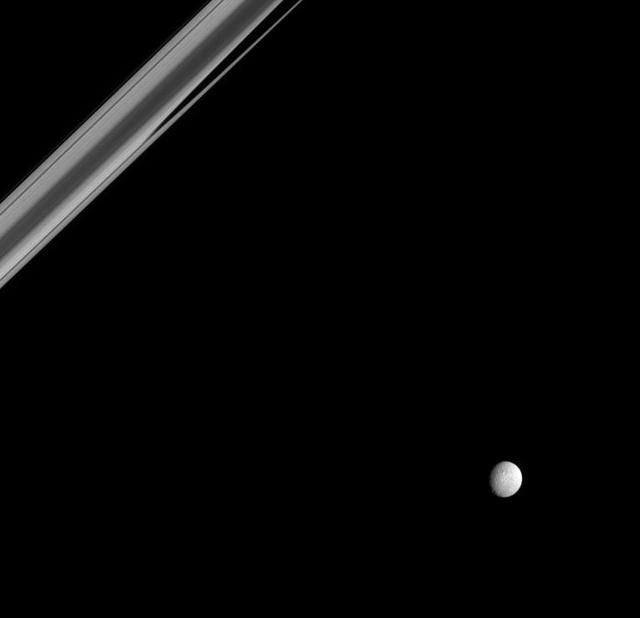

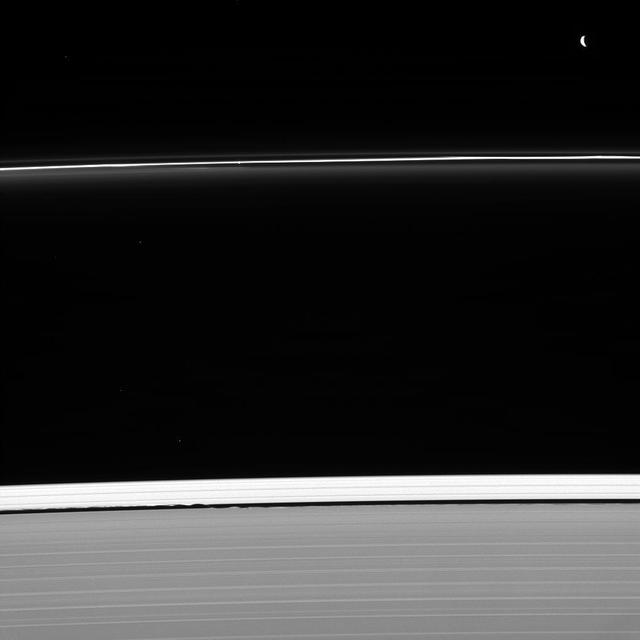

The Cassini spacecraft looks across the unlit ringplane as Mimas glides silently in front of Dione

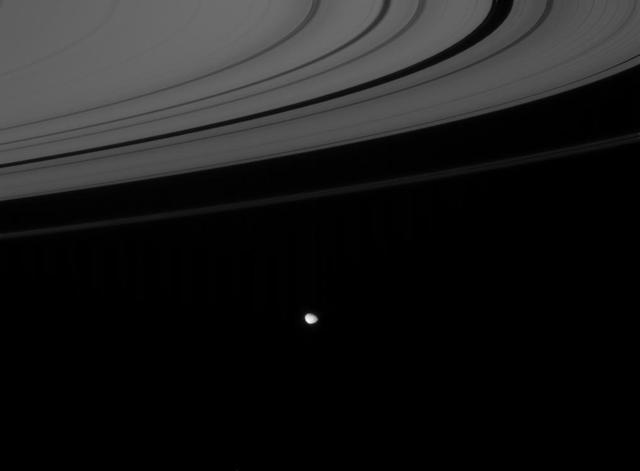

Cassini gazes down toward Saturn unilluminated ringplane to find Janus hugging the outer edge of rings

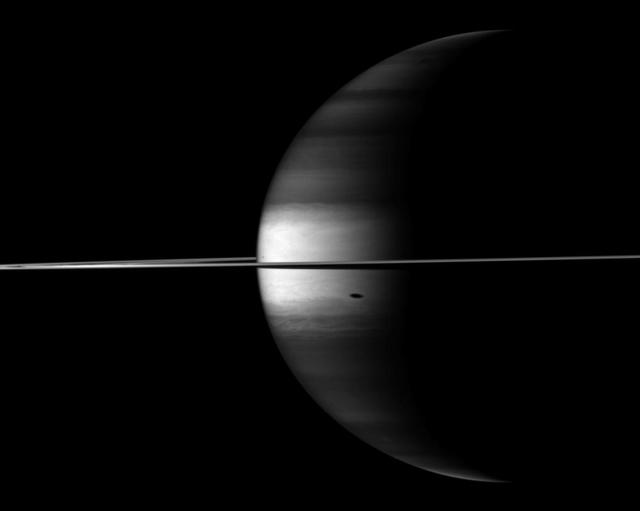

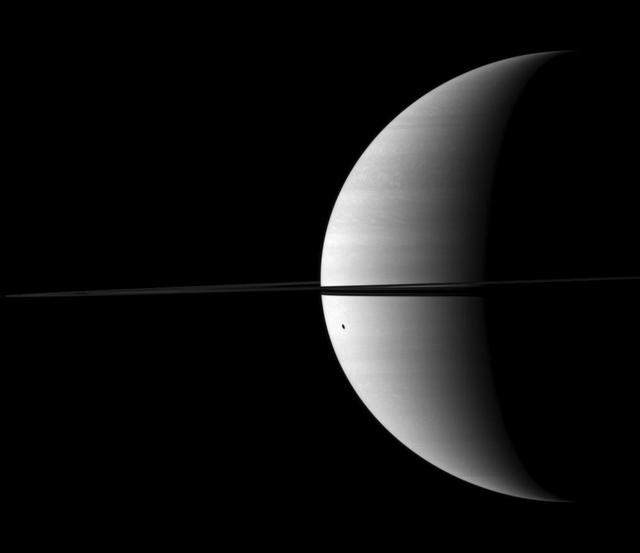

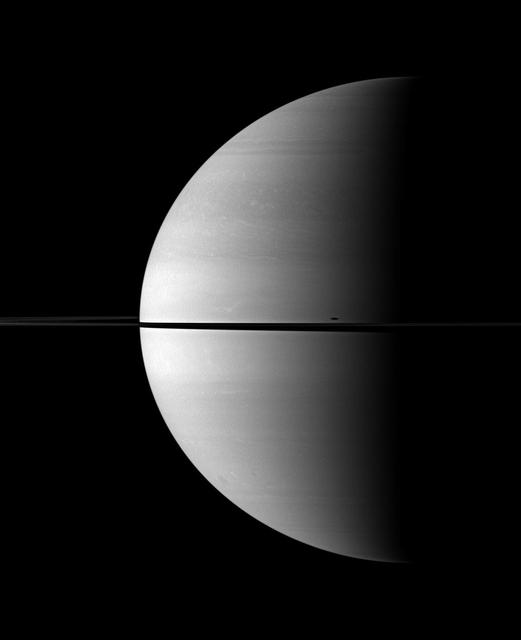

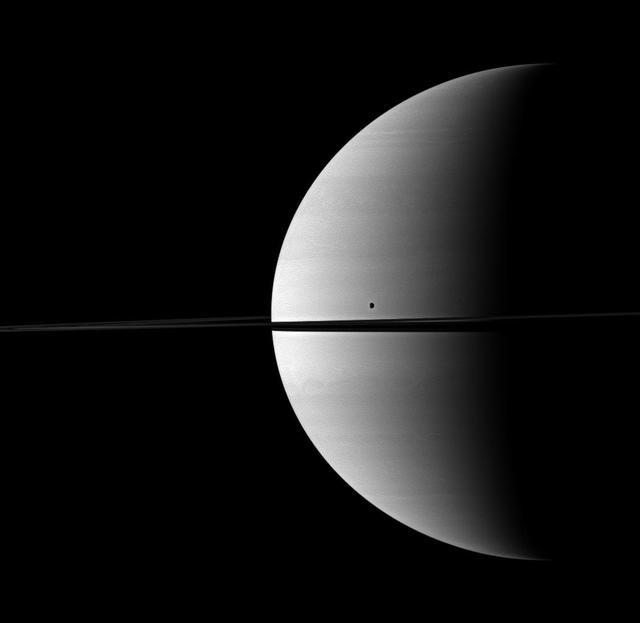

Appearing like a freckle on the face of Saturn, a shadow from the moon Enceladus blemishes the planet just below the ringplane in this NASA Cassini spacecraft image.

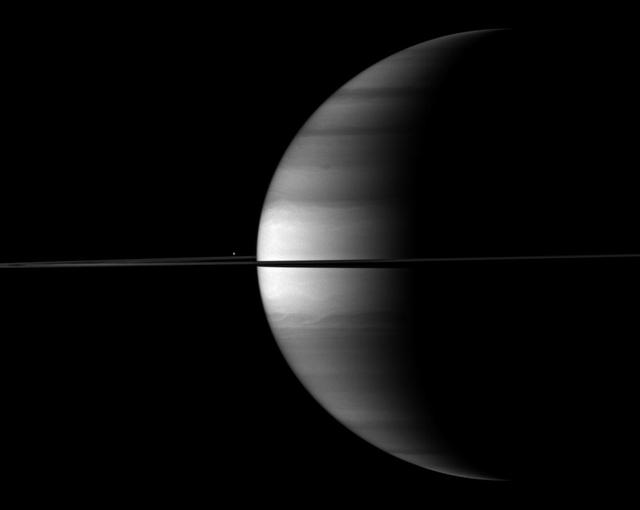

NASA Cassini spacecraft camera looks in near-infrared light at a dramatic view of Saturn, its ringplane and the shadows of a couple of its moons.

This fortunate view sights along Saturn ringplane to capture three moons aligned in a row: Dione at left, Prometheus at center and Epimetheus at right

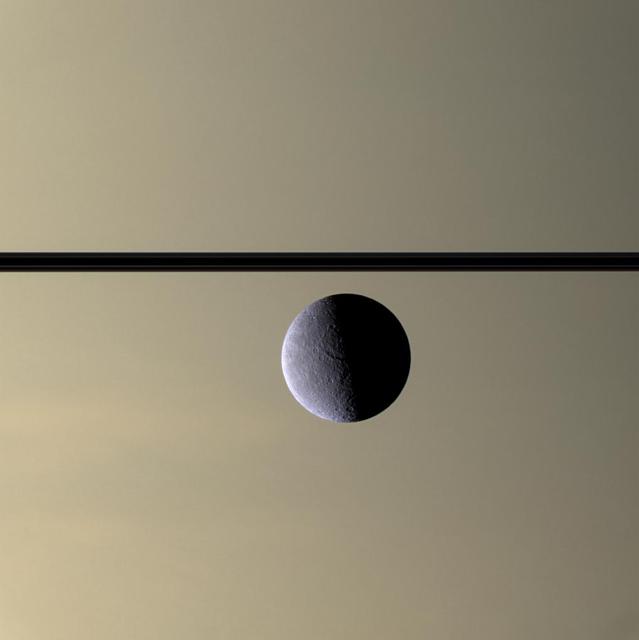

Dione steps in front of Tethys for a few minutes in an occultation, or mutual event. These events occur frequently for the Cassini spacecraft when it is orbiting close to the ringplane

Pan is nearly lost within Saturn rings in this view captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft of a small section of the rings from just above the ringplane.

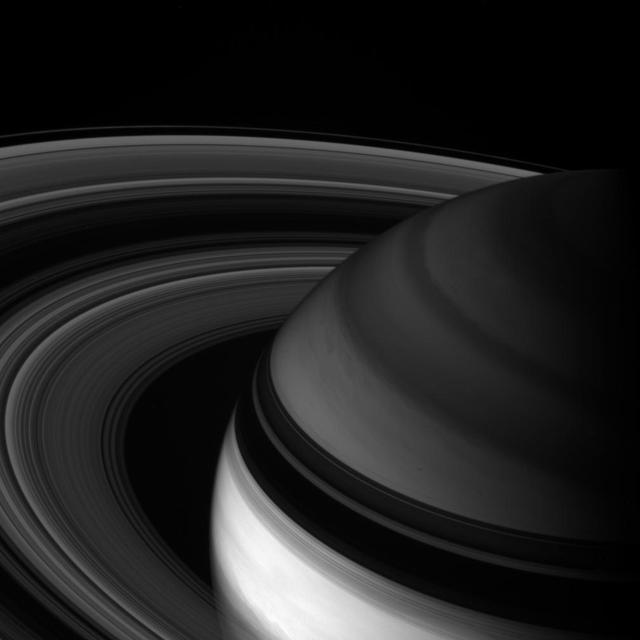

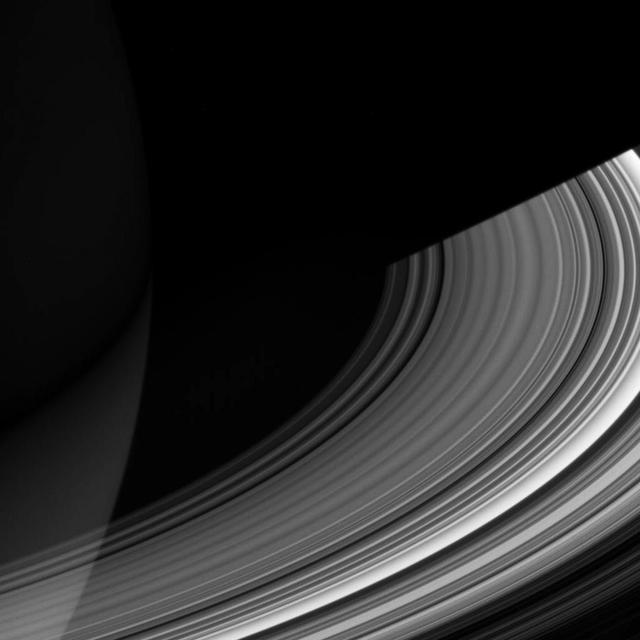

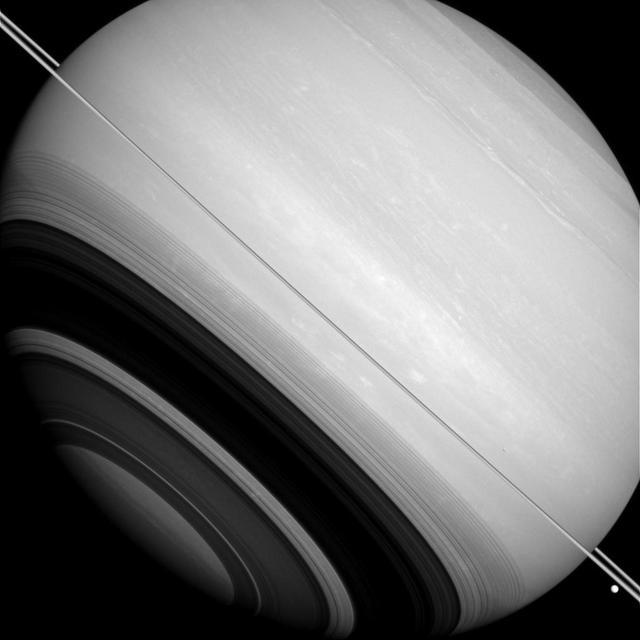

This view, acquired by NASA Cassini spacecraft, looks toward the unilluminated side of Saturn rings from about 47 degrees below the ringplane.

From beneath the ringplane, the Cassini spacecraft takes stock of Saturn southern skies and peeks through the rings and beyond their shadows at the northern latitudes

The diminutive moon Mimas can be found hiding in the middle of this view of a crescent of Saturn bisected by rings in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. Mimas appears as a dark speck just about the ringplane near the center of the image. Th

The Cassini spacecraft looks toward Rhea cratered, icy landscape with the dark line of Saturn ringplane and the planet murky atmosphere as a background. Rhea is Saturn second-largest moon, at 1,528 kilometers 949 miles across.

Saturn moon Enceladus orbits serenely before a backdrop of clouds roiling the atmosphere the planet in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft. This view looks toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings from just above the ringplane.

Whiffs of cloud dance in Saturn atmosphere, while the dim crescent of Rhea 1,528 kilometers, or 949 miles across hangs in the distance. The dark ringplane cuts a diagonal across the top left corner of this view

This infrared view from high above Saturn ringplane highlights the contrast in the cloud bands, the dimly glowing rings and their shadows on the gas giant planet. The overall effect is stirring

Dione shadow is elongated as it is cast onto the round shape of Saturn in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft. The moon is not visible here. This view looks toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings from just above the ringplane.

Graceful giant Saturn poses with a few of the small worlds it holds close. From this viewpoint the Cassini spacecraft can see across the entirety of the planet shadow on the rings, to where the ringplane emerges once again into sunlight

The moon Tethys occupies the right foreground of this Saturnian scene. This view from NASA Cassini spacecraft looks toward the anti-Saturn side of Tethys and toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings from just above the ringplane.

The highly reflective moon Enceladus appears as a bright dot beyond a crescent Saturn in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft. Enceladus is visible above the ringplane to the left of the center of the image.

The shadow of Saturn moon Mimas is elongated across the planet in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft. The moon itself is not shown, but the shadow appears just above the ringplane on the right of the image.

Cassini looks toward northern latitudes on Saturn and out across the ringplane. This infrared view probes clouds beneath the hazes that obscure the planet depths in natural color views

Rhea and Enceladus hover in the distance beyond Saturn ringplane. Enceladus left, bathed in icy particles from Saturn E ring, appears noticeably brighter than Rhea

Cassini has Mimas and Pandora on its side as it gazes across the ringplane at distant Tethys. The two smaller moons were on the side of the rings closer to Cassini when this image was taken.

This view was taken from above the ringplane and looks toward the unlit side of the rings. Here, the probe gazes upon Titan in the distance beyond Saturn and its dark and graceful rings

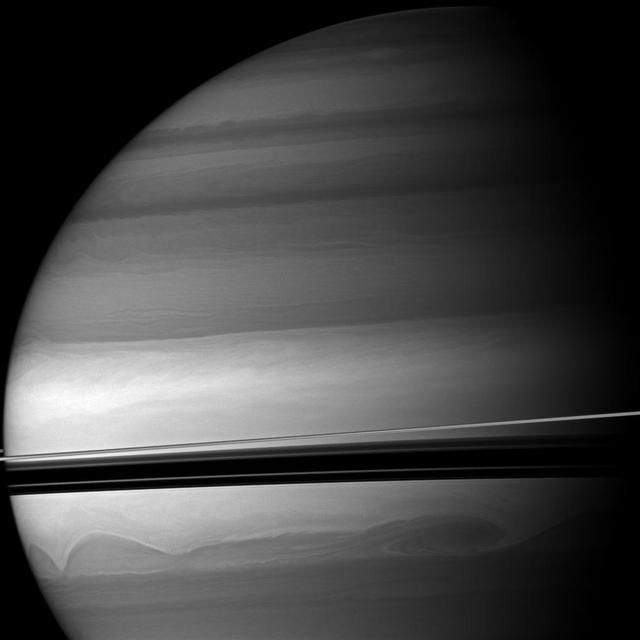

Huge clouds swirl through the southern latitudes of Saturn where the rings cast dramatic shadows. This view from NASA Cassini spacecraft looks toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings from just above the ringplane.

The shadow of Saturn moon Dione, cast onto the planet, is elongated in dramatic fashion in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. The moon itself does not appear here, but the shadow can be seen south of the ringplane.

Epimetheus floats in the distance below center, showing only the barest hint of its irregular shape. Pandora hides herself in the ringplane, near upper right, appearing as little more than a bump

The moon Tethys stands out as a tiny crescent of light in front of the dark of Saturn night side. Tethys can be seen above the ringplane on the far right of this NASA Cassini spacecraft image.

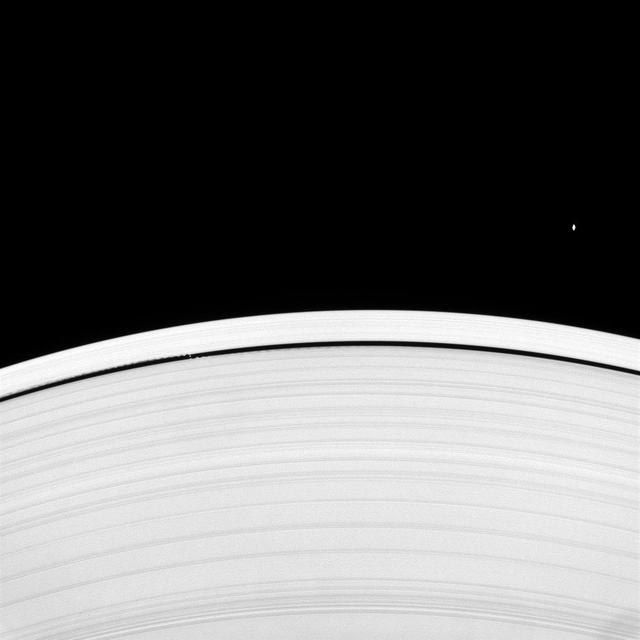

Looking upward from beneath the ringplane, the Cassini spacecraft spies Saturn's "wave maker" and "flying saucer" moons. Daphnis (8 kilometers, or 5 miles across at its widest point) and its gravitationally induced edge waves are seen at left within the Keeler Gap. The equatorial bulge on Atlas (30 kilometers, or 19 miles across at its widest point) is clearly visible here. See PIA06237 and PIA08405 for additional images and information about these two moons. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 16 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on April 22, 2008. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 898,000 kilometers (558,000 miles) from Saturn. Image scale is about 5 kilometers (3 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA09907

Saturn shares its space with its moon Tethys in this scene captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. Tethys can be seen above the rings near the middle of the image. This view looks toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings from just above the ringplane.

With its dazzling rings, Saturn radiates a beauty and splendor like no other known world. Here, Cassini has captured the cool crescent of Saturn from above the ringplane, with the planet shadow cutting neatly across the many lanes of ice

<p> The Cassini spacecraft looks toward the unilluminated side of Saturn rings to spy on the moon Pan as it cruises through the Encke Gap. </p> <p> This view looks toward the rings from about 13 degrees above the ringplane. At the top of the image

Janus peeks out from beneath the ringplane, partially lit here by reflected light from Saturn. A couple of craters can be seen on the moon surface. To the right, two faint clumps of material can be seen in the dynamic F ring

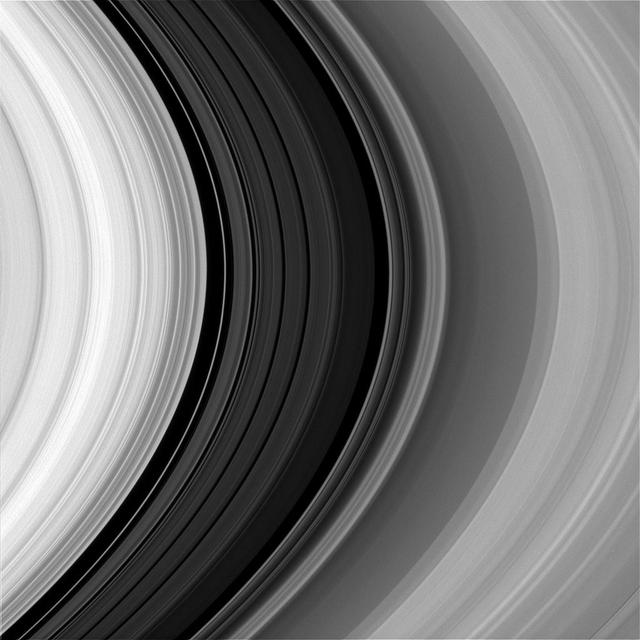

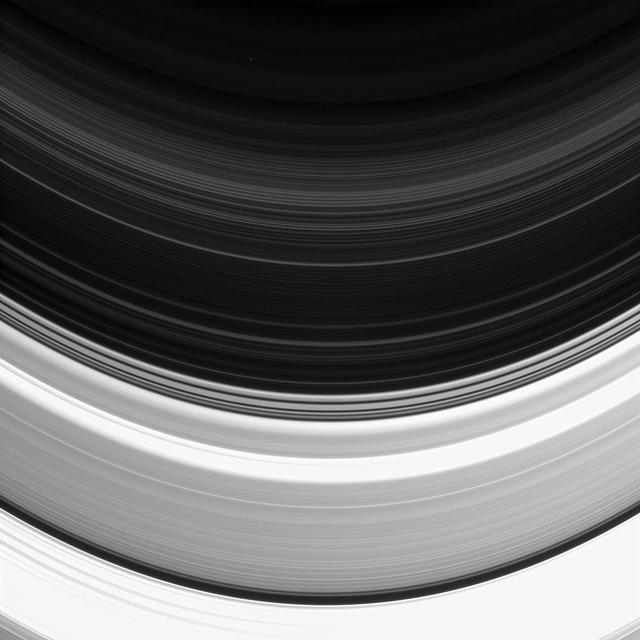

This view looks down onto the unlit side of Saturn ringplane. It nicely shows a near-arm/far-arm brightness asymmetry in the B ring: The near arm of the B ring is notably darker from this viewing geometry than is the far arm

This moody portrait of Saturn captures a razor-thin ringplane bisecting the clouds of the bright equatorial region. The rings cast dark, shadowy bands onto the planet's northern latitudes. At left, Dione (1,126 kilometers, or 700 miles across) is a tiny sunlit orb against the planet's dark side. The image was taken in polarized infrared light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Dec. 7, 2005 at a distance of approximately 3.1 million kilometers (1.9 million miles) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 96 degrees. Image scale is 179 kilometers (111 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA07673

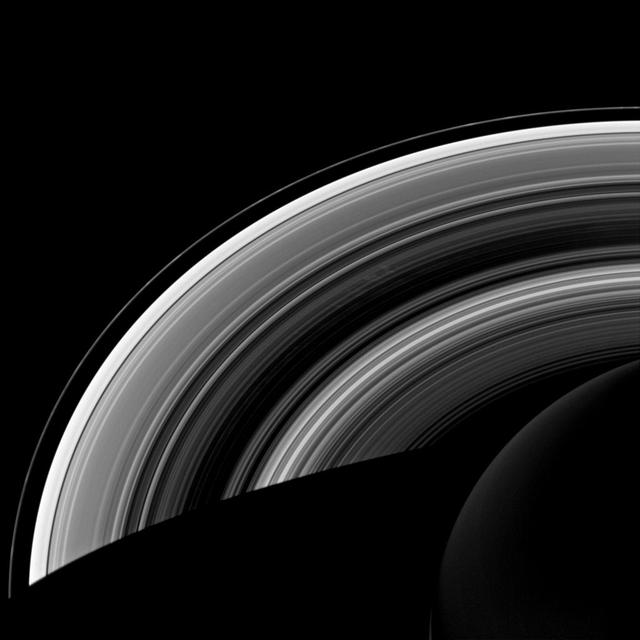

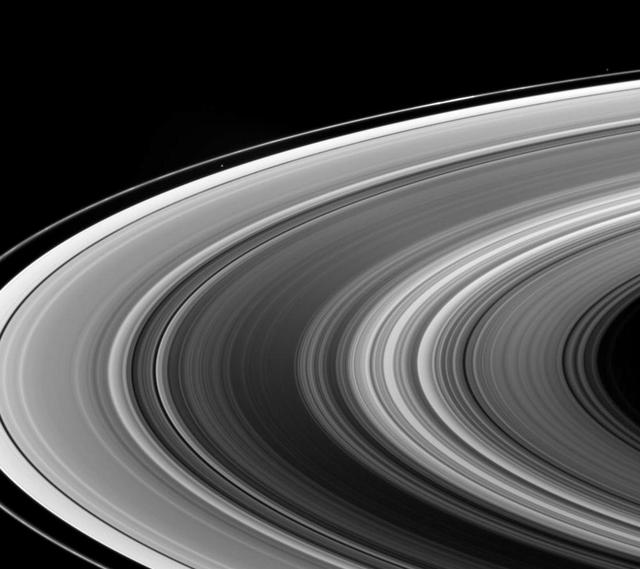

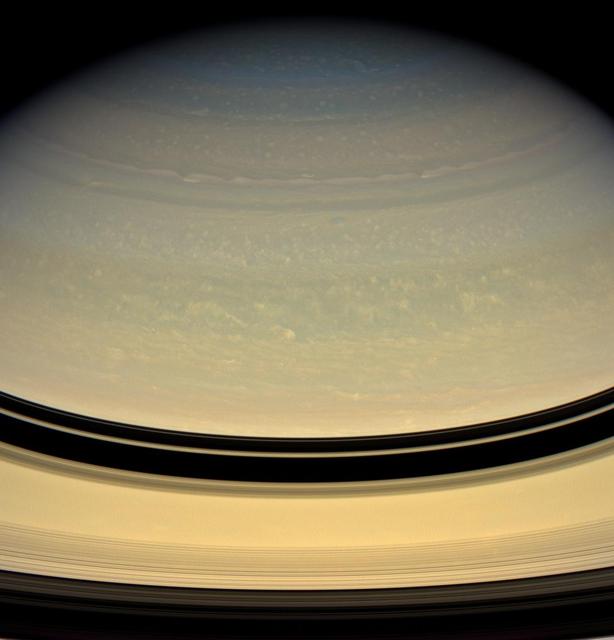

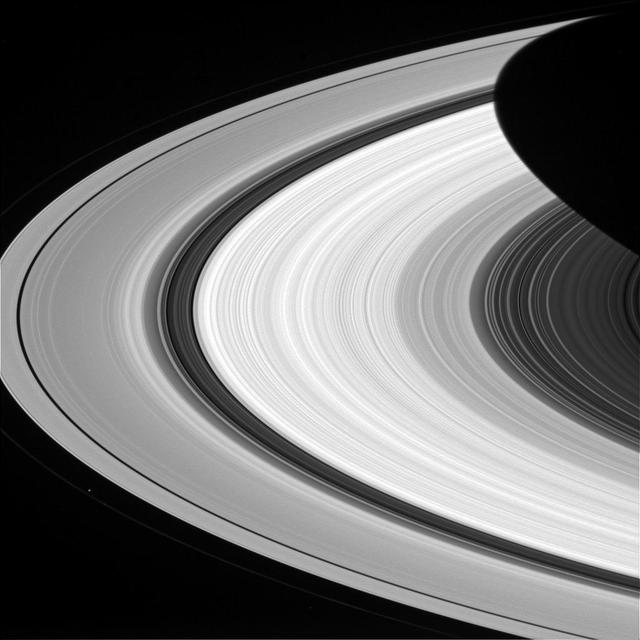

Although the rings lack the many colors of the rainbow, they arc across the sky of Saturn. From equatorial locations on the planet, they'd appear very thin since they would be seen edge-on. Closer to the poles, the rings would appear much wider; in some locations (for parts of the Saturn's year), they would even block the sun for part of each day. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 10, 2017. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 680,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 128 degrees. Image scale is 43 miles (69 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21339

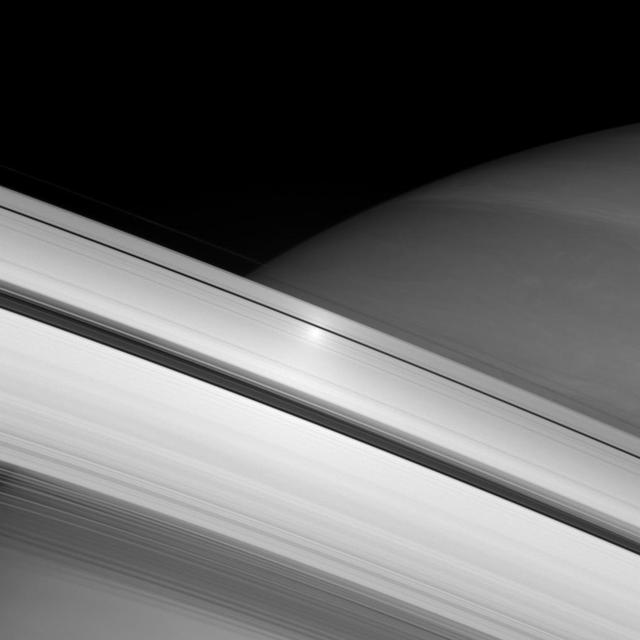

A surge in brightness appears on the rings directly opposite the Sun from the Cassini spacecraft. This "opposition surge" travels across the rings as the spacecraft watches. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 9 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on June 12, 2007 using a spectral filter sensitive to wavelengths of infrared light centered at 853 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 524,374 kilometers (325,830 miles) from Saturn. Image scale is 31 kilometers (19 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA08992

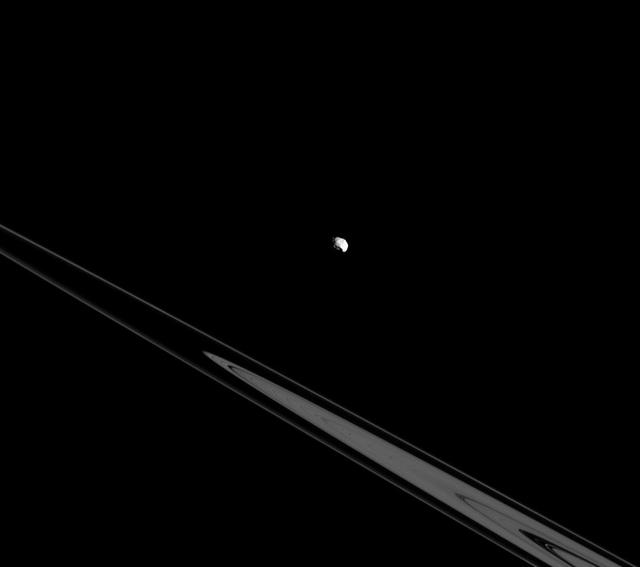

Although Janus should be the least lonely of all moons -- sharing its orbit with Epimetheus -- it still spends most of its orbit far from other moons, alone in the vastness of space. Janus (111 miles or 179 kilometers across) and Epimetheus have the same average distance from Saturn, but they take turns being a little closer or a little farther from Saturn, swapping positions approximately every 4 years. See PIA08348 for more. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 4, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.6 million miles (2.5 million kilometers) from Janus and at a Sun-Janus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 91 degrees. Image scale is 9 miles (15 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18315

Saturn's innermost moon Pan orbits the giant planet seemingly alone in a ring gap its own gravity creates. Pan (17 miles, or 28 kilometers across) maintains the Encke Gap in Saturn's A ring by gravitationally nudging the ring particles back into the rings when they stray in the gap. Scientists think similar processes might be at work as forming planets clear gaps in the circumstellar disks from which they form. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 38 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 3, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 2 million miles (3.2 million kilometers) from Pan and at a Sun-Pan-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 56 degrees. Image scale is 12 miles (19 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18281

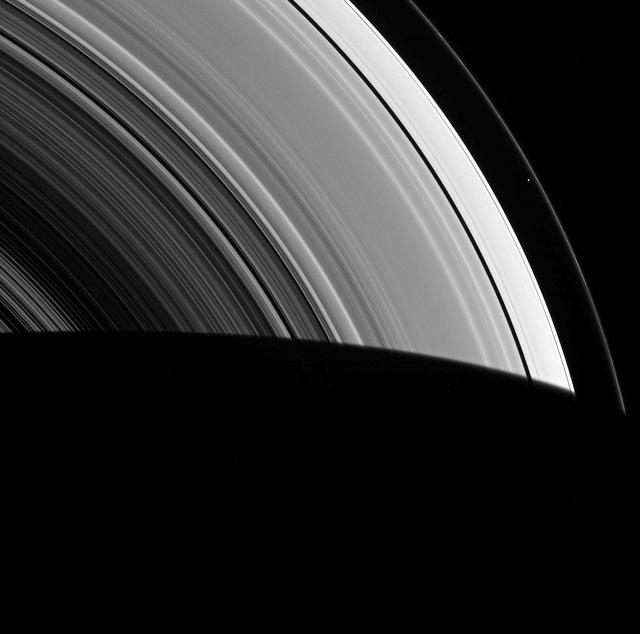

Seen by NASA Cassini spacecraft within the vast expanse of Saturn rings, Prometheus appears as little more than a dot. But that little moon still manages to shape the F ring, confining it to its narrow domain. Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across) and its fellow moon Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers across) orbit beside the F ring and keep the ring from spreading outward through a process dubbed "shepherding." This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 45 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on March 8, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 533,000 miles (858,000 kilometers) from Prometheus and at a Sun-Prometheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 90 degrees. Image scale is 32 miles (51 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18272

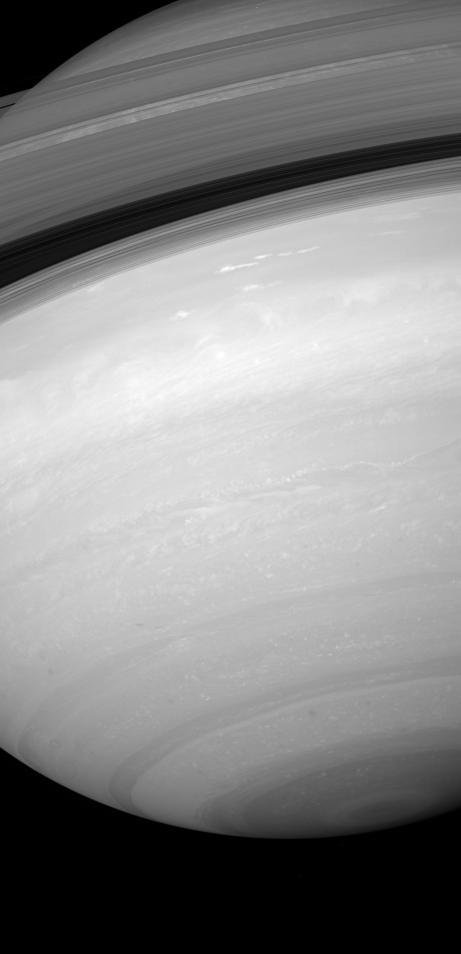

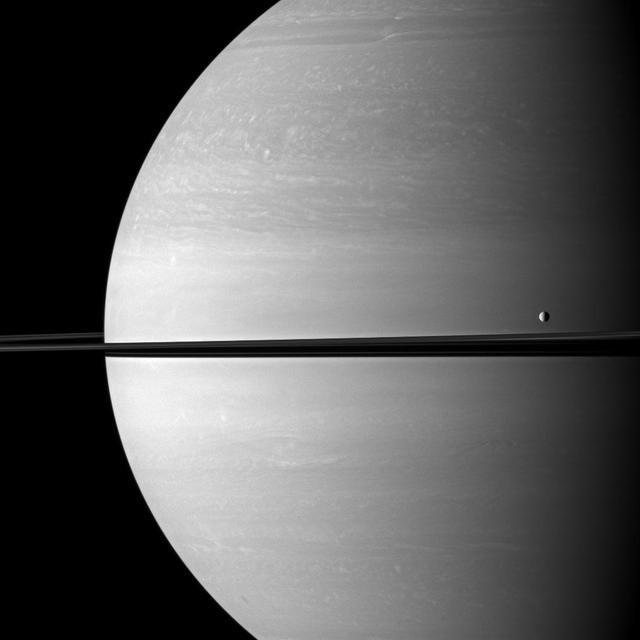

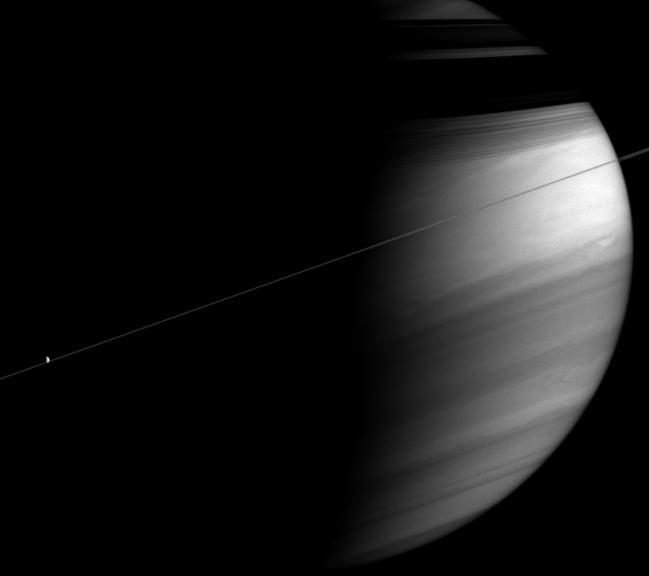

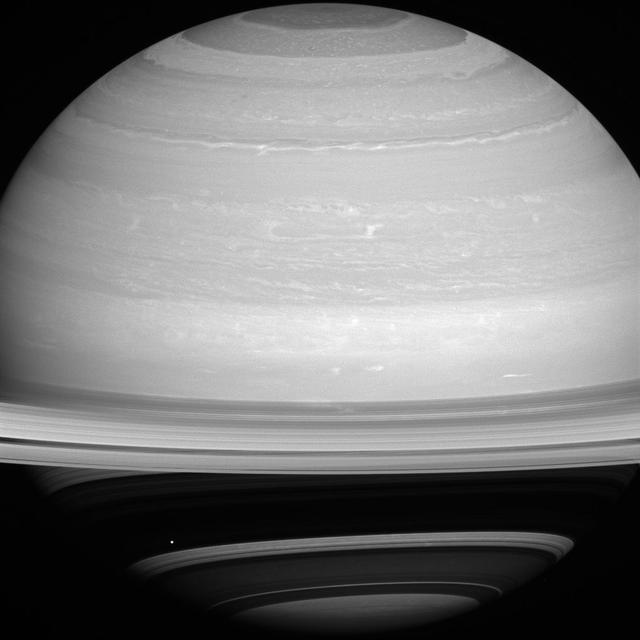

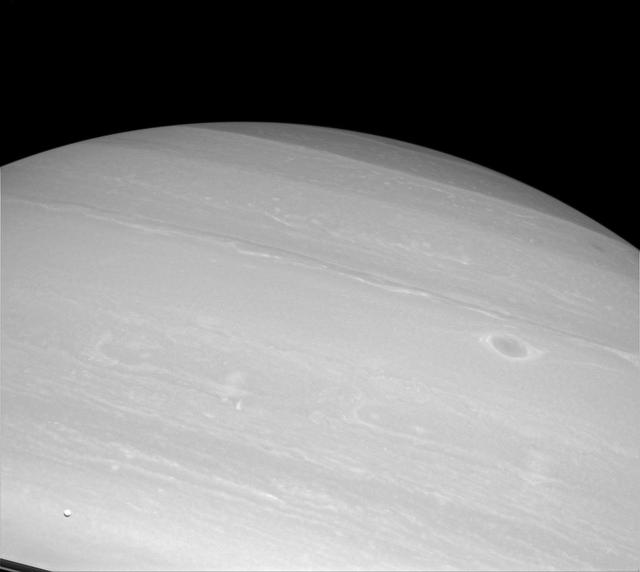

Saturn many cloud patterns, swept along by high-speed winds, look as if they were painted on by some eager alien artist in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft. With no real surface features to slow them down, wind speeds on Saturn can top 1,100 mph (1,800 kph), more than four times the top speeds on Earth. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 29 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 4, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.8 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 68 miles (109 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18280

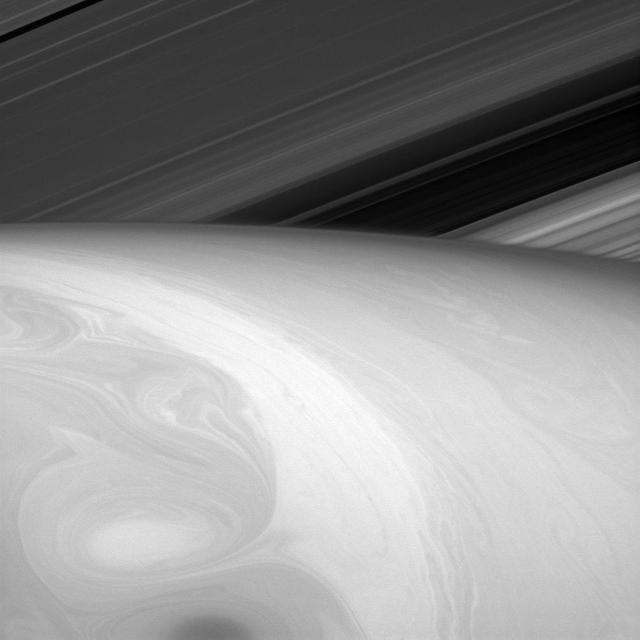

Saturn's surface is painted with swirls and shadows. Each swirl here is a weather system, reminding us of how dynamic Saturn's atmosphere is. Images taken in the near-infrared (like this one) permit us to peer through Saturn's methane haze layer to the clouds below. Scientists track the clouds and weather systems in the hopes of better understanding Saturn's complex atmosphere - and thus Earth's as well. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Feb. 8, 2015 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 794,000 miles (1.3 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 47 miles (76 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18311

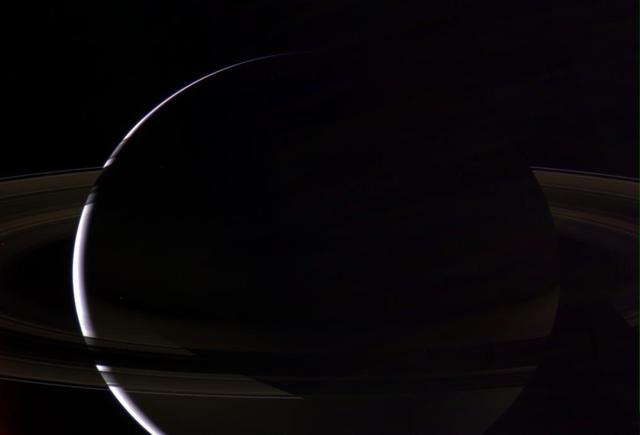

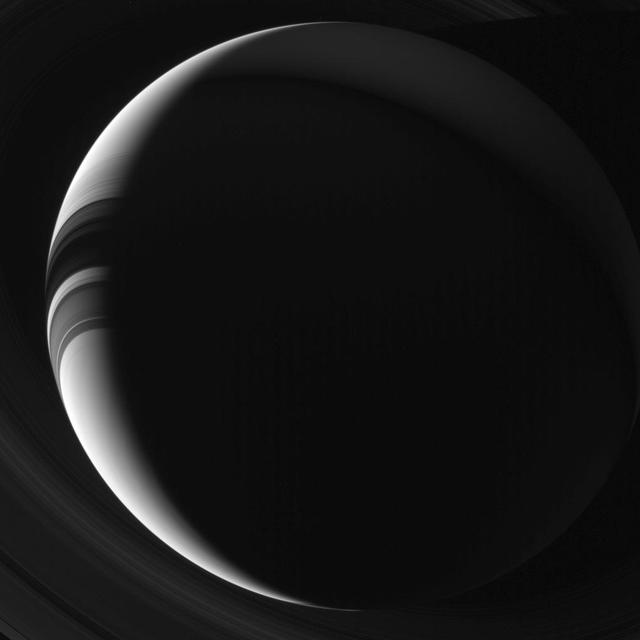

Saturn appears to NASA Cassini cameras as a thin, sunlit crescent in this unearthly view. Citizens of Earth, being so much closer to the Sun than Saturn, never get to enjoy a view of Saturn like this without the aid of our robot envoys. Parts of the night side of Saturn show faint illumination due to light reflected off the rings back onto the planet, an effect dubbed "ringshine." This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 43 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 4, 2013. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 75 miles (120 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18276

Nature is an artist, and this time she seems to have let her paints swirl together a bit. What the viewer might perceive to be Saturn's surface is really just the tops of its uppermost cloud layers. Everything we see is the result of fluid dynamics. Astronomers study Saturn's cloud dynamics in part to test and improve our understanding of fluid flows. Hopefully, what we learn will be useful for understanding our own atmosphere and that of other planetary bodies. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 25 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in red light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Aug. 23, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.7 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 23 degrees. Image scale is 63 miles (102 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18290

In reality, Janus and the rings both orbit Saturn and are only weakly connected to each other through their mutual gravitational tugs. At specific locations in the rings, these gravitational tugs result in orbital resonances, which lead to some beautiful waves being created in the rings. See PIA10452 for an example. Janus is 111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Dec. 5, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2.0 million kilometers) from Janus and at a Sun-Janus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 35 degrees. Image scale is 7 miles (12 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18304

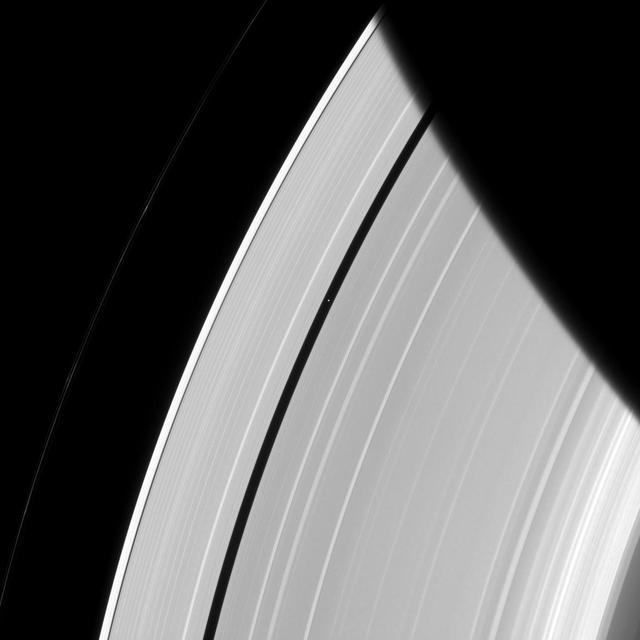

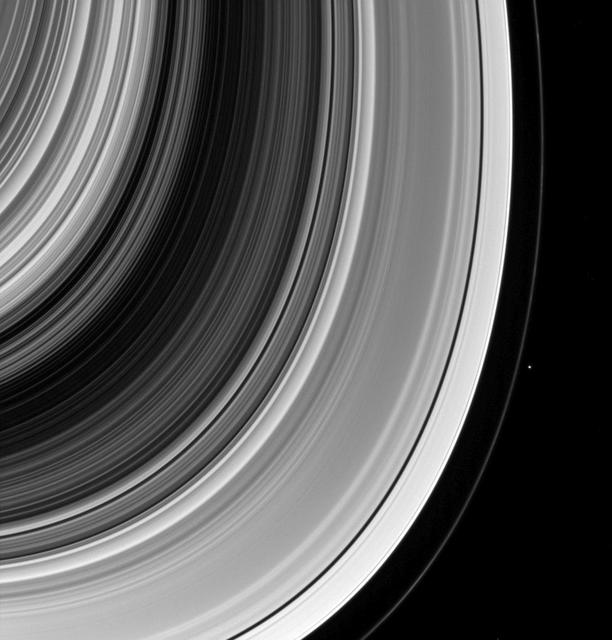

What's that bright point of light in the outer A ring? It's a star, bright enough to be visible through the ring! Quick, make a wish! This star -- seen in the lower right quadrant of the image -- was not captured by coincidence, it was part of a stellar occultation. By monitoring the brightness of stars as they pass behind the rings, scientists using this powerful observation technique can inspect detailed structures within the rings and how they vary with location. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 44 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Oct. 8, 2013. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.8 million kilometers) from the rings and at a Sun-Rings-Spacecraft, or phase, angle of 96 degrees. Image scale is 6.8 miles (11 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18297

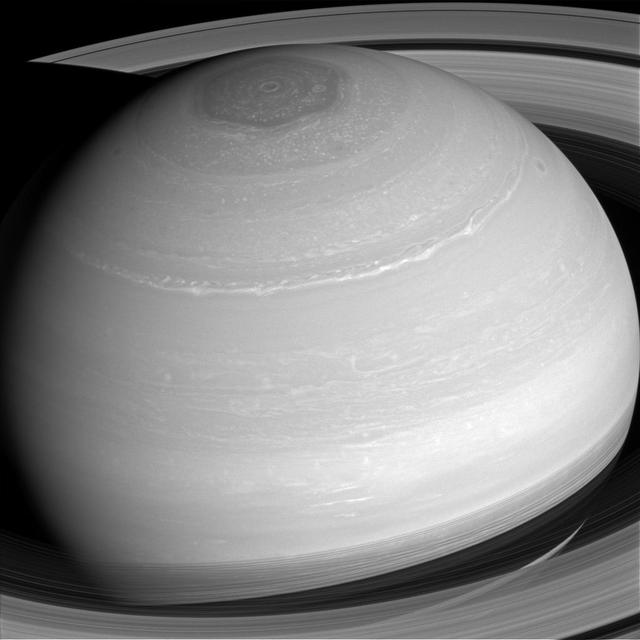

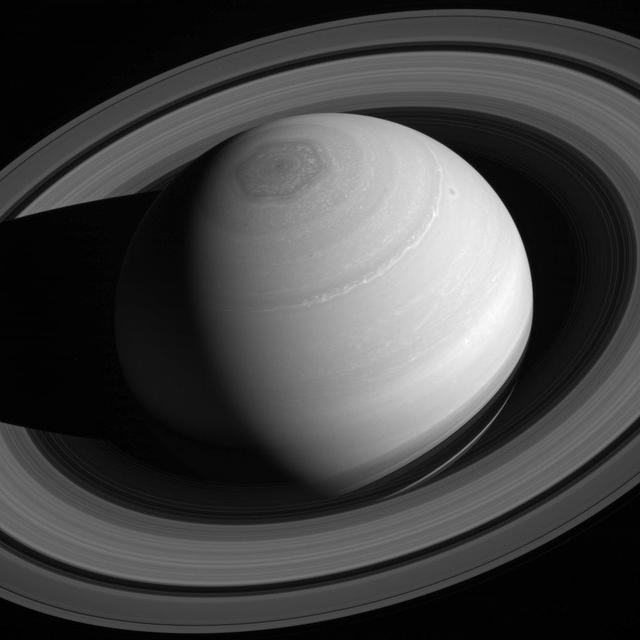

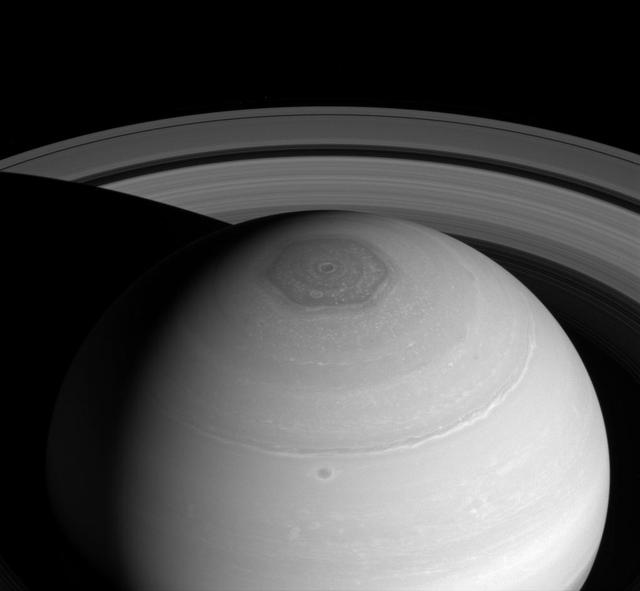

Saturn reigns supreme, encircled by its retinue of rings. Although all four giant planets have ring systems, Saturn's is by far the most massive and impressive. Scientists are trying to understand why by studying how the rings have formed and how they have evolved over time. Also seen in this image is Saturn's famous north polar vortex and hexagon. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 37 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on May 4, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 2 million miles (3 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 110 miles (180 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18278

Bright puffs and ribbons of cloud drift lazily through Saturn's murky skies. In contrast to the bold red, orange and white clouds of Jupiter, Saturn's clouds are overlain by a thick layer of haze. The visible cloud tops on Saturn are deeper in its atmosphere due to the planet's cooler temperatures. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 18 degrees above the ringplane. Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. The images were acquired with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 15, 2008 at a distance of approximately 1.5 million kilometers (906,000 miles) from Saturn. Image scale is 84 kilometers (52 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA09910

Although it appears empty from a distance, the Encke gap in Saturn A ring has three ringlets threaded through it, two of which are visible here from NASA Cassini spacecraft. Each ringlet has dynamical structure such as the clumps seen in this image. The clumps move about and even appear and disappear, in part due to the gravitational effects of Pan. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 27 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 11, 2013. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 199,000 miles (321,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 121 degrees. Image scale is 1 mile (2 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18277

Both luminous and translucent, the C ring sweeps out of the darkness of Saturn's shadow and obscures the planet at lower left. The ring is characterized by broad, isolated bright areas, or "plateaus," surrounded by fainter material. This view looks toward the unlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. North on Saturn is up. The dark, inner B ring is seen at lower right. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Dec. 15, 2006 at a distance of approximately 632,000 kilometers (393,000 miles) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 56 degrees. Image scale is 34 kilometers (21 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA08855

Nature is often more complex and wonderful than it first appears. For example, although it looks like a simple hexagon, this feature surrounding Saturn's north pole is really a manifestation of a meandering polar jet stream. Scientists are still working to understand more about its origin and behavior. For more on the hexagon, see PIA11682. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 33 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in red light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 24, 2013. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 605,000 miles (973,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 19 degrees. Image scale is 36 miles (58 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18287

The F ring shepherd Pandora is captured here by NASA Cassini spacecraft along with other well-known examples of Saturn moons shaping the rings. From the narrow F ring, to the gaps in the A ring, to the Cassini Division, Saturn's rings are a masterpiece of gravitational sculpting by the moons. Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers across), along with its fellow shepherd Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across), helps confine the F ring and keep it from spreading. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 31 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on March 8, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 533,000 miles (858,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 63 degrees. Image scale is 32 miles (51 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18271

NASA Cassini spacecraft captures three magnificent sights at once: Saturn north polar vortex and hexagon along with its expansive rings. The hexagon, which is wider than two Earths, owes its appearance to the jet stream that forms its perimeter. The jet stream forms a six-lobed, stationary wave which wraps around the north polar regions at a latitude of roughly 77 degrees North. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 37 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 2, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.2 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 43 degrees. Image scale is 81 miles (131 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18274

With this view, Cassini captured one of its last looks at Saturn and its main rings from a distance. The Saturn system has been Cassini's home for 13 years, but that journey is nearing its end. Cassini has been orbiting Saturn for nearly a half of a Saturnian year but that journey is nearing its end. This extended stay has permitted observations of the long-term variability of the planet, moons, rings, and magnetosphere, observations not possible from short, fly-by style missions. When the spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004, the planet's northern hemisphere, seen here at top, was in darkness, just beginning to emerge from winter. Now at journey's end, the entire north pole is bathed in the continuous sunlight of summer. Images taken on Oct. 28, 2016 with the wide angle camera using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this color view. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 25 degrees above the ringplane. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 870,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 50 miles (80 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21345

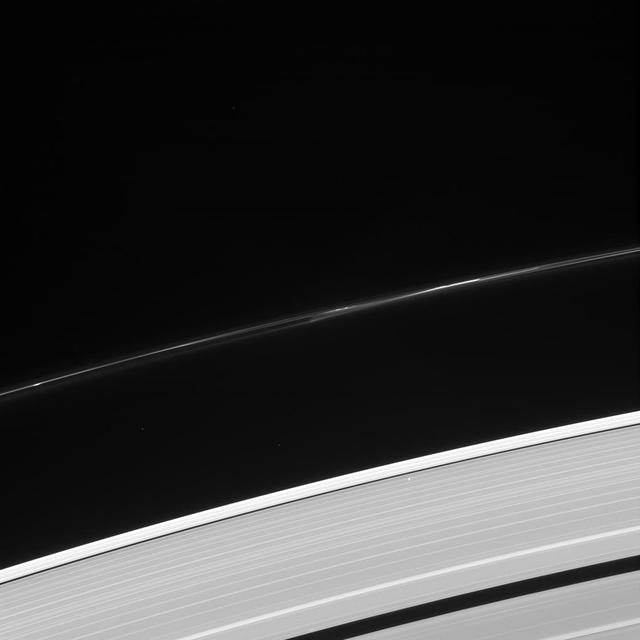

Saturn's main rings, seen here on their "lit" face, appear much darker than normal. That's because they tend to scatter light back toward its source -- in this case, the Sun. Usually, when taking images of the rings in geometries like this, exposures times are increased to make the rings more visible. Here, the requirement to not over-expose Saturn's lit crescent reveals just how dark the rings actually become. Scientists are interested in images in this sunward-facing ("high phase") geometry because the way that the rings scatter sunlight can tell us much about the ring particles' physical make-up. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 6 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Jan. 12, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 152 degrees. Image scale is 86 miles (138 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18294

As if trying to get our attention, Mimas is positioned against the shadow of Saturn's rings, bright on dark. As we near summer in Saturn's northern hemisphere, the rings cast ever larger shadows on the planet. With a reflectivity of about 96 percent, Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers across) appears bright against the less-reflective Saturn. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 10 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 13, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.8 million kilometers) from Saturn and approximately 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) from Mimas. Image scale is 67 miles (108 kilometers) per pixel at Saturn and 60 miles (97 kilometers) per pixel at Mimas. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18282

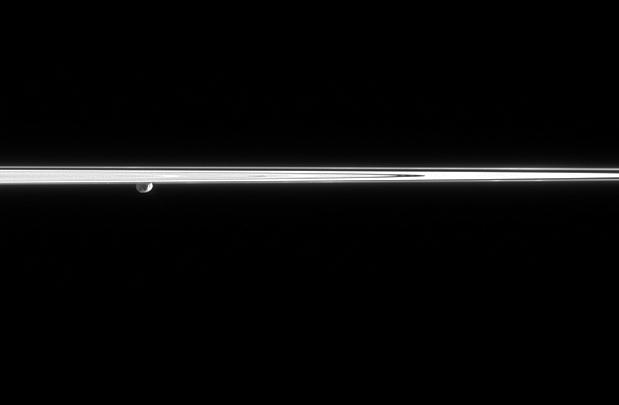

Although Epimetheus appears to be lurking above the rings here, it's actually just an illusion resulting from the viewing angle. In reality, Epimetheus and the rings both orbit in Saturn's equatorial plane. Inner moons and rings orbit very near the equatorial plane of each of the four giant planets in our solar system, but more distant moons can have orbits wildly out of the equatorial plane. It has been theorized that the highly inclined orbits of the outer, distant moons are remnants of the random directions from which they approached the planets they orbit. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about -0.3 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 26, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 500,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) from Epimetheus and at a Sun-Epimetheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 62 degrees. Image scale is 3 miles (5 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18342

If your eyes could only see the color red, this is how Saturn's rings would look. Many Cassini color images, like this one, are taken in red light so scientists can study the often subtle color variations of Saturn's rings. These variations may reveal clues about the chemical composition and physical nature of the rings. For example, the longer a surface is exposed to the harsh environment in space, the redder it becomes. Putting together many clues derived from such images, scientists are coming to a deeper understanding of the rings without ever actually visiting a single ring particle. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 11 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in red light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Dec. 6, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 870,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 27 degrees. Image scale is 5 miles (8 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18301

Prometheus is caught in the act of creating gores and streamers in the F ring. Scientists believe that Prometheus and its partner-moon Pandora are responsible for much of the structure in the F ring as shown by NASA Cassini spacecraft. The orbit of Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across) regularly brings it into the F ring. When this happens, it creates gores, or channels, in the ring where it entered. Prometheus then draws ring material with it as it exits the ring, leaving streamers in its wake. This process creates the pattern of structures seen in this image. This process is described in detail, along with a movie of Prometheus creating one of the streamer/channel features, in PIA08397. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 8.6 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 11, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.3 million miles (2.1 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 147 degrees. Image scale is 8 miles (13 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18270

Much as its name implies, tiny Epimetheus (Greek for hindsight) was discovered in hindsight. Astronomers originally thought that Janus and Epithemeus were the same object. Only later did astronomers realize that there are in fact two bodies sharing the same orbit. Janus (111 miles or 179 kilometers across) and Epimetheus (70 miles or 113 kilometers) have the same average distance from Saturn, but they take turns being a little closer or a little farther from Saturn, swapping positions approximately every 4 years. See PIA08348 for more. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 29 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 1, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.8 million miles (2.9 million kilometers) from Epimetheus and at a Sun-Epimetheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 89 degrees. Image scale is 11 miles (17 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18305

Although solid-looking in many images, Saturn's rings are actually translucent. In this picture, we can glimpse the shadow of the rings on the planet through (and below) the A and C rings themselves, towards the lower right hand corner. For centuries people have studied Saturn's rings, but questions about the structure and composition of the rings lingered. It was only in 1857 when the physicist James Clerk Maxwell demonstrated that the rings must be composed of many small particles and not solid rings around the planet, and not until the 1970s that spectroscopic evidence definitively showed that the rings are composed mostly of water ice. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 12, 2014 in near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 24 degrees. Image scale is 85 miles (136 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18295

When Galileo first observed Venus displaying a crescent phase, he excitedly wrote to Kepler (in anagram) of Venus mimicking the moon-goddess. He would have been delirious with joy to see Saturn and Titan, seen in this image, doing the same thing. More than just pretty pictures, high-phase observations -- taken looking generally toward the Sun, as in this image -- are very powerful scientifically since the way atmospheres and rings transmit sunlight is often diagnostic of compositions and physical states. In this example, Titan's crescent nearly encircles its disk due to the small haze particles high in its atmosphere refracting the incoming light of the distant Sun. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 3 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in violet light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 11, 2013. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.7 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 154 degrees. Image scale is 64 miles (103 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18291

The Cassini spacecraft captures a rare family photo of three of Saturn's moons that couldn't be more different from each other! As the largest of the three, Tethys (image center) is round and has a variety of terrains across its surface. Meanwhile, Hyperion (to the upper-left of Tethys) is the "wild one" with a chaotic spin and Prometheus (lower-left) is a tiny moon that busies itself sculpting the F ring. To learn more about the surface of Tethys (660 miles, or 1,062 kilometers across), see PIA17164 More on the chaotic spin of Hyperion (168 miles, or 270 kilometers across) can be found at PIA07683 And discover more about the role of Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across) in shaping the F ring in PIA12786. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 1 degree above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 14, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (1.9 million kilometers) from Tethys and at a Sun-Tethys-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 22 degrees. Image scale is 7 miles (11 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18283

Saturn's graceful lanes of orbiting ice -- its iconic rings -- wind their way around the planet to pass beyond the horizon in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft. And diminutive Pandora, scarcely larger than a pixel here, can be seen orbiting just beyond the F ring in this image. Also in this image is the gap between Saturn's cloud tops and its innermost D ring through which Cassini would pass 22 times before ending its mission in spectacular fashion in Sept. 15, 2017. Scientists scoured images of this region, particularly those taken at the high phase (spacecraft-ring-Sun) angles, looking for material that might pose a hazard to the spacecraft. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 12, 2017. Pandora was brightened by a factor of 2 to increase its visibility. The view was obtained at a distance to Saturn of approximately 581,000 miles (935,000 kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 35 miles (56 kilometers) per pixel. The distance to Pandora was 691,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) for a scale of 41 miles (66 kilometers) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21352

Tiny Epimetheus is dwarfed by adjacent slivers of the A and F rings. But is it really? Looks can be deceiving! There is approximately 10 to 20 times more mass in that tiny dot than in the piece of the A ring visible in this image! In total, Saturn's rings have about as much mass as a few times the mass of the moon Mimas. (This mass estimate comes from measuring the waves raised in the rings by moons like Epimetheus.) The rings look physically larger than any moon because the individual ring particles are very small, giving them a large surface area for a given mass. Epimetheus (70 miles or 113 kilometers across), on the other hand, has a small surface area per mass compared to the rings, making it look deceptively small. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Dec. 5, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometers) from Epimetheus and at a Sun-Epimetheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 40 degrees. Image scale is 7 miles (12 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18302

Reflected sunlight is the source of the illumination for visible wavelength images such as the one above. However, at longer infrared wavelengths, direct thermal emission from objects dominates over reflected sunlight. This enabled instruments that can detect infrared radiation to observe the pole even in the dark days of winter when Cassini first arrived at Saturn and Saturn's northern hemisphere was shrouded in shadow. Now, 13 years later, the north pole basks in full sunlight. Close to the northern summer solstice, sunlight illuminates the previously dark region, permitting Cassini scientists to study this area with the spacecraft's full suite of imagers. This view looks toward the northern hemisphere from about 34 degrees above Saturn's ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 25, 2017 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 274,000 miles (441,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 111 degrees. Image scale is 16 miles (26 kilometers) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21351

Two masters of their craft are caught at work shaping Saturn's rings. Pandora (upper right) sculpts the F ring, as does nearby Prometheus (not seen in this image). Meanwhile, Daphnis is busy holding open the Keeler gap (bottom center), its presence revealed here by the waves it raises on the gap's edge. The faint moon is located where the inner and outer waves appear to meet. Also captured in this image, shining through the F ring above the image center, is a single star. Although gravity is by its very nature an attractive force, moons can interact with ring particles in such a way that they effectively push ring particles away from themselves. Ring particles experience tiny gravitational "kicks" from these moons and subsequently collide with other ring particles, losing orbital momentum. The net effect is for moons like Pandora (50 miles or 81 kilometers across) and Daphnis (5 miles or 8 kilometers across) to push ring edges away from themselves. The Keeler gap is the result of just such an interaction. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 50 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 30, 2013. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18298

Are the moons tiny or are the rings vast? Both, in a way! The moons visible in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft, Pandora and Atlas, are quite small by astronomical standards, but the rings are also enormous. From one side of the planet to the other, the A ring stretches over 170,000 miles 270,000 km. Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers, across) orbits in the vicinity of the F ring, along with neighboring Prometheus, which is not visible in this image. These moons interact frequently with the narrow F ring, producing channels and streamers and other interesting features. Atlas (19 miles, or 30 kilometers across) orbits between the A ring and F ring in the Roche division. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 34 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 17, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.7 million miles (2.8 million kilometers) from Pandora and at a Sun-Pandora-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 110 degrees. Image scale is 11 miles (17 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18279

Befitting moons named for brothers, the moons Prometheus and Epimetheus share a lot in common. Both are small, icy moons that orbit near the main rings of Saturn. But, like most brothers, they also assert their differences: while Epimetheus is relatively round for a small moon, Prometheus is elongated in shape, similar to a lemon. Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across) orbits just outside the A ring - seen here upper-middle of the image - while Epimetheus (70 miles, 113 kilometers across) orbits farther out - seen in the upper-left, doing an orbital two-step with its partner, Janus. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 28 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 9, 2013. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 557,000 miles (897,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 11 degrees. Image scale is 33 miles (54 kilometers) per pixel. Prometheus and Epimetheus have been brightened by a factor of 2 relative to the rest of the image to enhance their visibility. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18286

Sometimes at Saturn you can see things almost as if from every angle at once, the way a Cubist might imagine things. For example, in this image, we're seeing Saturn's A ring in the lower part of the image and the limb of Saturn in the upper. In addition, the rings cast their shadows onto the portion of the planet imaged here, creating alternating patterns of light and dark. This pattern is visible even through the A ring, which, unlike the core of the nearby B ring, is not completely opaque. The ring shadows on Saturn often appear to cross the surface at confusing angles in close-ups like this one. The visual combination of Saturn's oblateness, the varying opacity of its rings and the shadows cast by those rings, sometimes creates elaborate and complicated patterns from Cassini's perspective. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Dec. 5, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 7 miles (11 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18303

Saturn is circled by its rings (seen nearly edge-on in this image), as well as by the moons Tethys (the large bright body near the lower right hand corner of this image) and Mimas (seen as a slight crescent against Saturn's disk above the rings, at about 4 o'clock). The shadows of the rings, each ringlet delicately recorded across Saturn's face, also circle around Saturn's south pole. Although the rings and larger moons of Saturn mostly orbit very near the planet's equatorial plane, this image shows that they do not all lie precisely in the orbital plane. Part of the reason that Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers across) and Tethys (660 miles, or 1062 kilometers across) appear above and below the ring plane because their orbits are slightly inclined (about 1 to 1.5 degrees) relative to the rings. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from slightly above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 14, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.7 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 23 degrees. Image scale is 63 miles (102 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18288

From afar, Saturn's rings look like a solid, homogenous disk of material. But upon closer examination from Cassini, we see that there are varied structures in the rings at almost every scale imaginable. Structures in the rings can be caused by many things, but often times Saturn's many moons are the culprits. The dark gaps near the left edge of the A ring (the broad, outermost ring here) are caused by the moons (Pan and Daphnis) embedded in the gaps, while the wider Cassini division (dark area between the B ring and A ring here) is created by a resonance with the medium-sized moon Mimas (which orbits well outside the rings). Prometheus is seen orbiting just outside the A ring in the lower left quadrant of this image; the F ring can be faintly seen to the left of Prometheus. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 15 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in red light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Jan. 8, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 566,000 miles (911,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 37 degrees. Image scale is 34 miles (54 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18308

Not all of Saturn's rings are created equal: here the C and D rings appear side-by-side, but the C ring, which occupies the bottom half of this image, clearly outshines its neighbor. The D ring appears fainter than the C ring because it is comprised of less material. However, even rings as thin as the D ring can pose hazards to spacecraft. Given the high speeds at which Cassini travels, impacts with particles just fractions of a millimeter in size have the potential to damage key spacecraft components and instruments. Nonetheless, near the end of Cassini's mission, navigators plan to thread the spacecraft's orbit through the narrow region between the D ring and the top of Saturn's atmosphere. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 12 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 11, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 372,000 miles (599,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 133 degrees. Image scale is 2.2 miles (3.6 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18313

Enceladus (visible in the lower-left corner of the image) is but a speck before enormous Saturn, but even a small moon can generate big waves of excitement throughout the scientific community. Enceladus, only 313 miles (504 kilometers) across, spurts vapor jets from its south pole. The presence of these jets from Enceladus has been the subject of intense study since they were discovered by Cassini. Their presence may point to a sub-surface water reservoir. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 2 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Oct. 20, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 589,000 miles (948,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 26 degrees. Image scale is 35 miles (57 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18296

As Cassini hurtled toward its fatal encounter with Saturn, the spacecraft turned to catch this final look at Saturn's moon Pandora next to the thin line of the F ring. Over the course of its mission, Cassini helped scientists understand that Pandora plays a smaller role than they originally thought in shaping the narrow ring. When Cassini arrived at Saturn, many thought that Pandora and Prometheus worked together to shepherd the F ring between them, confining it and sculpting its unusual braided and kinked structures. However, data from Cassini show that the gravity of the two moons together actually stirs the F ring into a chaotic state, generating the "gap and streamer" structure. Recent models, supported by Cassini images, suggest that it is Prometheus alone, not Pandora, that confines the bulk of the F ring, aided by the particular characteristics of its orbit. Prometheus establishes stable locations for F ring material where the moon's own gravitational resonances are least cluttered by the perturbing influence of its sibling satellite, Pandora. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 28 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Sept. 14, 2017. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 360,000 miles (577,000 kilometers) from Pandora and at a Sun-Pandora-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 119 degrees. Image scale is about 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21355

People with similar jobs or interests hold conventions and meetings, so why shouldn't moons? Pandora, Prometheus, and Pan -- seen here, from right to left -- also appear to be holding some sort of convention in this image. Some moons control the structure of nearby rings via gravitational "tugs." The cumulative effect of the moon's tugs on the ring particles can keep the rings' edges from spreading out as they are naturally inclined to do, much like shepherds control their flock. Pan is a prototypical shepherding moon, shaping and controlling the locations of the inner and outer edges of the Encke gap through a mechanism suggested in 1978 to explain the narrow Uranian rings. However, though Prometheus and Pandora have historically been called "the F ring shepherd moons" due to their close proximity to the ring, it has long been known that the standard shepherding mechanism that works so well for Pan does not apply to these two moons. The mechanism for keeping the F ring narrow, and the roles played -- if at all -- by Prometheus and Pandora in the F ring's configuration are not well understood. This is an ongoing topic for study by Cassini scientists. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 29 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 2, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.6 million miles (2.6 million kilometers) from the rings and at a Sun-ring-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 86 degrees. Image scale is 10 miles (15 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18306