This image shows stone stripes on the side of a volcanic cone on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. The stripes are made of small rock fragments and they are aligned downhill as freeze-thaw cycles have lifted them up and out of the finer-grained regolith, and moved them to the sides, forming stone stripes. This site is at about 13,450-foot (4,100-meter) altitude on the mountain. For scale, the rock cluster toward the bottom right of the image is approximately 1 foot (30 centimeters) wide. The image was taken in 1999 by R. E. Arvidson. Such ground texture has been seen in recent images from NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22219

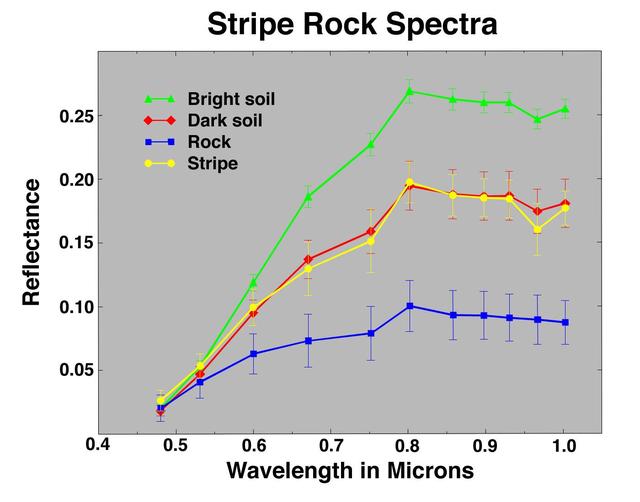

Stripe Rock Spectra

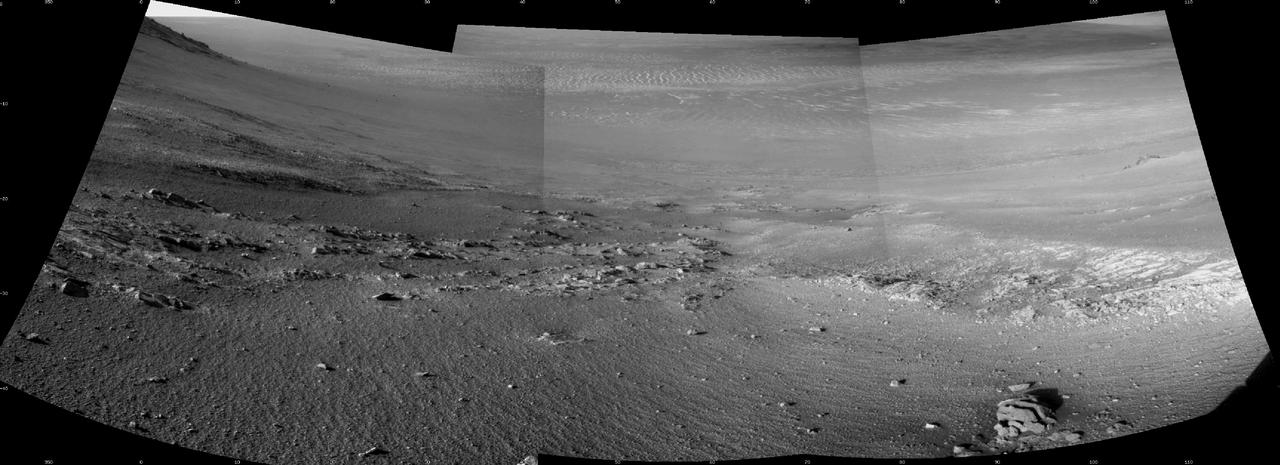

Textured rows on the ground in this portion of "Perseverance Valley" are under investigation by NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity, which used its Navigation Camera (Navcam) to take the component images of this downhill-looking scene. The rover took this image on Jan. 4, 2018, during the 4,958th Martian day, or sol, of its work on Mars, looking downhill from a position about one-third of the way down the valley. Perseverance Valley descends the inboard slope of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. A view on the same sol with the rover's front Hazard Avoidance Camera includes ground even closer to the rover at this site. Opportunity was still working close by as it reached the mission's Sol 5,000 (Feb. 16, 2018). In the portion of the valley seen here, soil and gravel have been shaped into a striped pattern in the foreground and partially bury outcrops visible in the midfield. The long dimensions of the stripes are approximately aligned with the downhill direction. The striped pattern resembles a type of feature on Earth (such as on Hawaii's Mauna Kea) that is caused by repeated cycles of freezing and thawing, though other possible origins are also under consideration for the pattern in Perseverance Valley. The view is spans from north on the left to east-southeast on the right. For scale, the foreground rock clump in the lower right is about 11 inches (28 centimeters) in width. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22217

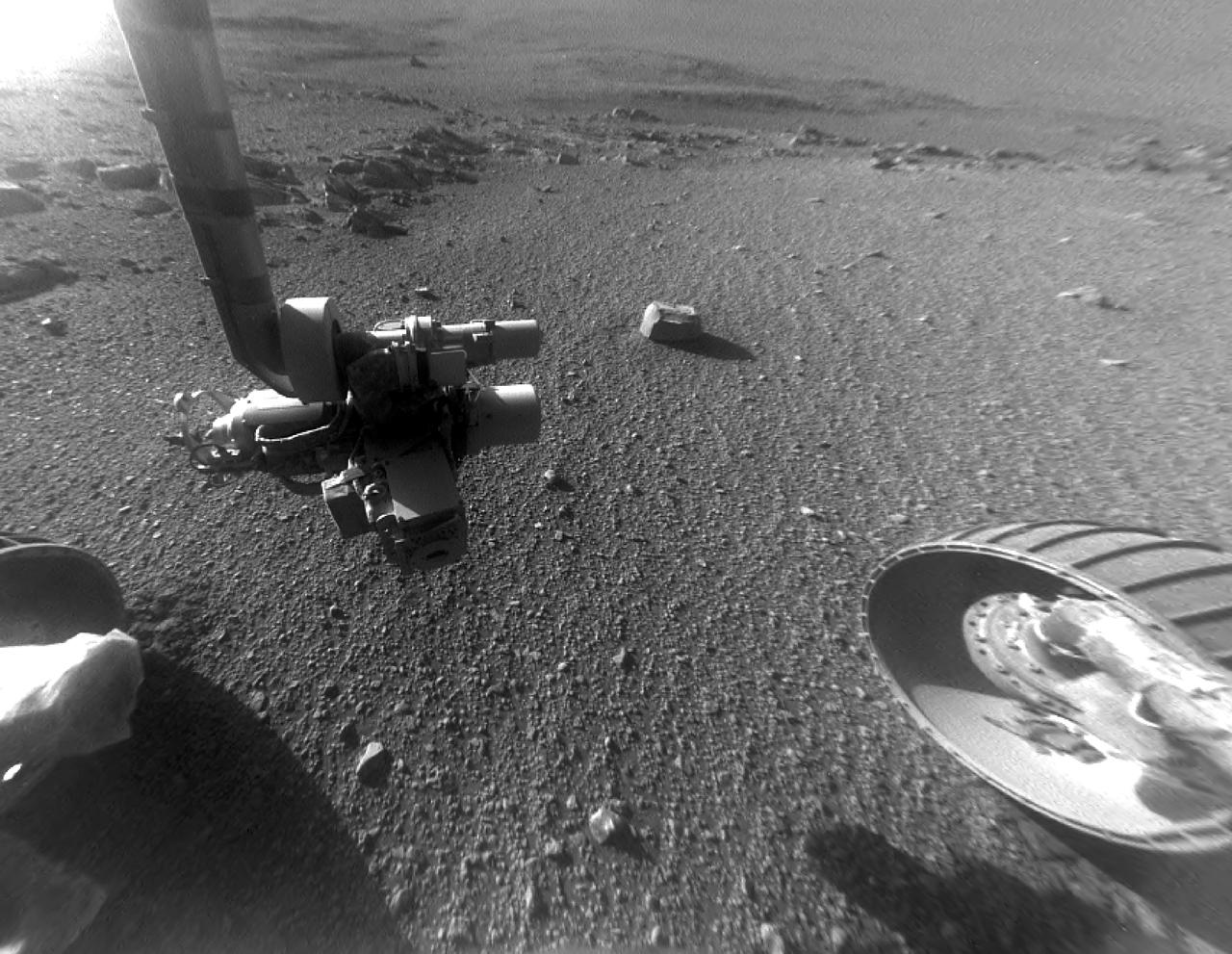

This late-afternoon view from the front Hazard Avoidance Camera on NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity shows a pattern of rock stripes on the ground, a surprise to scientists on the rover team. Approaching the 5,000th Martian day or sol, of what was planned as a 90-sol mission, Opportunity is still providing new discoveries. This image was taken inside "Perseverance Valley," on the inboard slope of the western rim of Endeavour Crater, on Sol 4958 (Jan. 4, 2018). Both this view and one taken the same sol by the rover's Navigation Camera look downhill toward the northeast from about one-third of the way down the valley, which extends about the length of two football fields from the crest of the rim toward the crater floor. The lighting, with the Sun at a low angle, emphasizes the ground texture, shaped into stripes defined by rock fragments. The stripes are aligned with the downhill direction. The rock to the upper right of the rover's robotic arm is about 2 inches (5 centimeters) wide and about 3 feet (1 meter) from the centerline of the rover's two front wheels. This striped pattern resembles features seen on Earth, including on Hawaii's Mauna Kea, that are formed by cycles of freezing and thawing of ground moistened by melting ice or snow. There, fine-grained fraction of the soil expands as it freezes, and this lifts the rock fragments up and to the sides. If such a process formed this pattern in Perseverance Valley, those conditions might have been present locally during a period within the past few million years when Mars' spin axis was at a greater tilt than it is now, and some of the water ice now at the poles was redistributed to lower latitudes. Other hypotheses for how these features formed are also under consideration, including high-velocity slope winds. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22218

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) was originally meant to track the movement of sand dunes near the North Pole of Mars, but what's on the ground in between the dunes is just as interesting! The ground has parallel dark and light stripes from upper left to lower right in this area. In the dark stripes, we see piles of boulders at regular intervals. What organized these boulders into neatly-spaced piles? In the Arctic back on Earth, rocks can be organized by a process called "frost heave." With frost heave, repeatedly freezing and thawing of the ground can bring rocks to the surface and organize them into piles, stripes, or even circles. On Earth, one of these temperature cycles takes a year, but on Mars it might be connected to changes in the planet's orbit around the Sun that take much longer. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22334

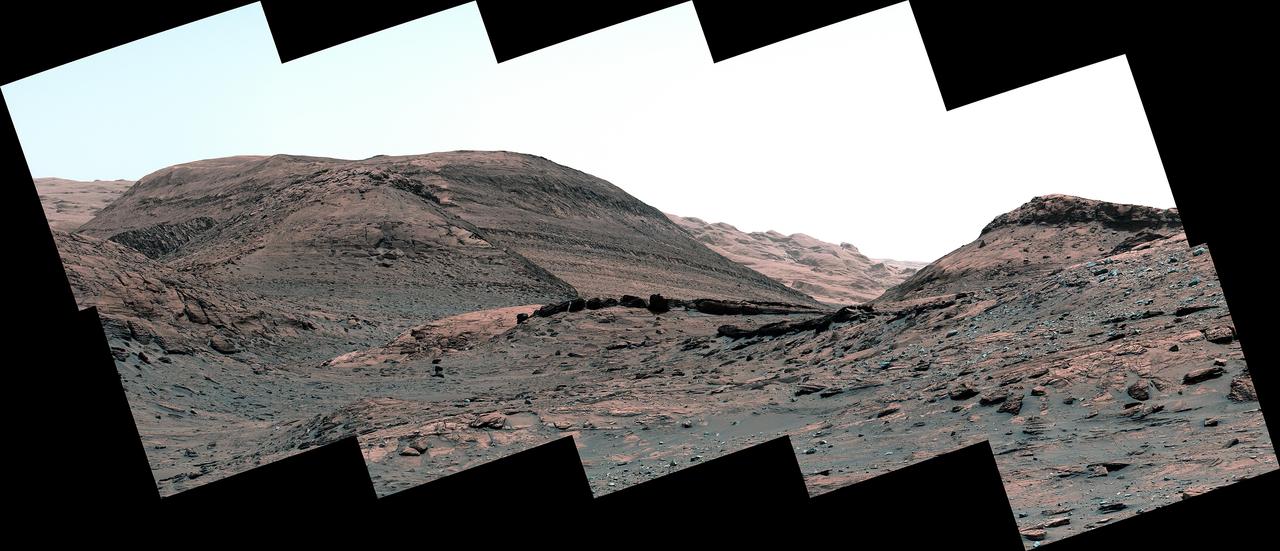

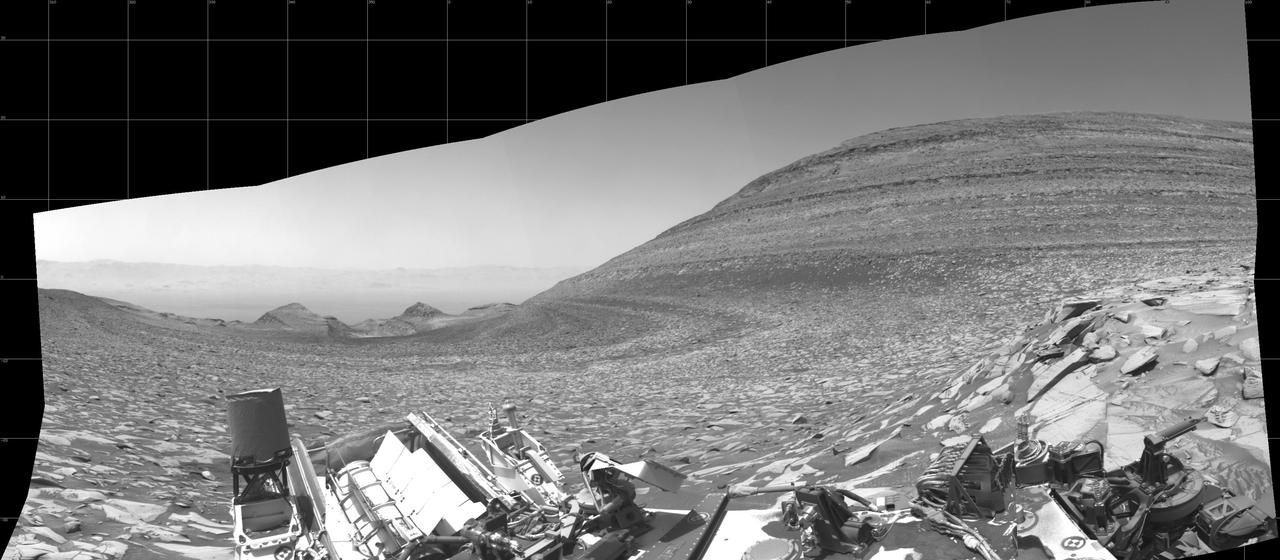

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover captured this view of a sulfate-bearing region ahead of its current location. Dark boulders near the center of the panorama are thought to have formed from sand deposited in ancient streams or ponds. Scattered gray rocks covering the hillside on the right are all that remain of a sandstone capping unit that once covered this area. This panorama is made up of 10 individual images that were captured by Curiosity's Mast Camera, or Mastcam, on May 2, 2022, the 3,462nd Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The images were stitched together after they were sent back to Earth. Behind the dark boulders – in the middle of the image – is a mountain that makes up part of the sulfate-bearing region; layers within this region can be seen as stripes across the mountainside. These layers represent an excellent record of how Mars' water and climate changed over time. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25367

This image shows sedimentary rock and sand within Danielson Crater, an impact crater 67 kilometers in diameter, located in the southwest Arabia Terra region of Mars. The rock was formed millions or billions of years ago when loose sediments settled into the crater, one layer at a time, and were later cemented in place. Cyclical variations in the sediment properties made some layers more resistant to erosion than others. After eons, these tougher layers protrude outward like stair steps. Across these steps, the winds have scattered sand (typically appearing darker and less red, i.e. "bluer" in contrast-enhanced color), giving rise to the zebra stripe-like patterns visible here. This image completes a stereo pair over this location, which will allow measurement of the thicknesses of these sedimentary layers. The layer thicknesses and how they vary through time can provide some insight into the processes, possibly linked to ancient climate, that deposited the layers so long ago. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23454

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover captured this panorama – showing the area it climbed to reach Gediz Vallis channel – using its left black-and-white navigation camera on Feb. 1, 2024, the 4,084th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The panorama is made up of 10 images that were stitched together after being sent back to Earth. At center is the slope Curiosity ascended, which is striped with alternating dark and light bands of sedimentary rock. Farther down the slope are two buttes: "Chenapau" on the left and "Orinoco" on the right. Farther still is the floor of Gale Crater, with the crater's rim in the far distance. At right rises a banded butte nicknamed "Kukenán." Since 2014, Curiosity has been ascending the foothills of Mount Sharp, which stands 3 miles (5 kilometers) above the floor of Gale Crater. The layers in this lower part of the mountain formed over millions of years under a changing Martian climate, providing scientists with a way to study how the presence of both water and the chemical ingredients required for life changed over time. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26247

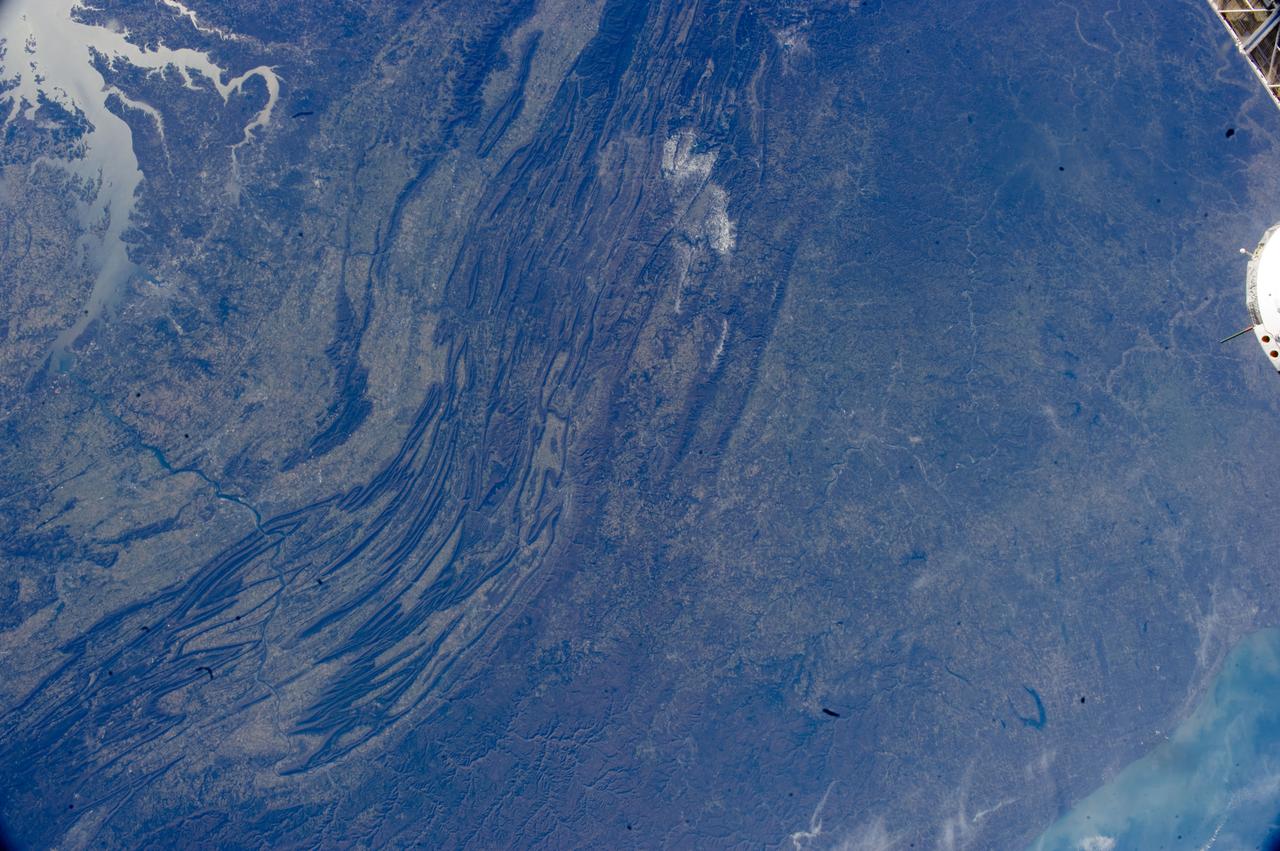

ISS033-E-022378 (17 Nov. 2012) --- The Appalachian Mountains in the eastern Unites States are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 33 crew member on the International Space Station. This regional view shows the striking visual effect of the valley-and-ridge topography of the Appalachian Mountains as viewed from orbit. The view shows more than 300 miles (500 kilometers) of this low mountain chain, from northeast Pennsylvania (lower left) to southern West Virginia, where a dusting of snow can be seen (top center). Sunglint reflections reveal detail of Chesapeake Bay and the great bend of the Potomac River. Cities are difficult to detect from space during daylight hours, so the sickle-shaped bend of the river is a good visual guide for station crew members trying to photograph the nation?s capital, Washington D.C. (upper left). The farm-dominated Piedmont Plateau is the light-toned area between the mountains and the bay. The Appalachian Mountains appear striped because the ridges are forested; providing a dense and dark canopy cover, while the valleys are farmed with crops that generally appear as lighter-toned areas. Geologically the valleys are the softer, more erodible rock layers, much the preferred places for human settlement. Not only do the larger rivers occupy the valley floors, but all the larger rivers flow in them, soils are thicker, slopes are gentle, and valleys are better protected from winter winds. According to scientists, rocks that form the valley-and-ridge province, as it is known, are relatively old (540-300 million years old), and were laid down in horizontal layers when North America was attached to Europe as the ancient supercontinent of Laurasia. During this time Gondwanaland ? an ancient supercontinent that included present-day Africa, India, South America, Australia and Antarctica - was approaching Laurasia under the influence of plate tectonics. The northwest coastline of modern Africa was the section of Gondwanaland that ?bumped up? against modern North America over a long period (320 ? 260 million years ago), according to scientists. The net result of the tectonic collision was the building of a major mountain chain, much higher than the present Appalachian range?in the process of which the flat-lying rock layers were crumpled up into a series of tight folds, at right angles to the advance of Gondwanaland. The collision also formed the singular supercontinent of Pangaea. The scientists say that, over the following 200 million years, Pangaea broke apart; the modern Atlantic Ocean formed; and erosion wore down the high mountains. What is left to see are the coastline of North America, and the eroded stumps of the mountain chain as the relatively low, but visually striking present-day Appalachian Mountains.

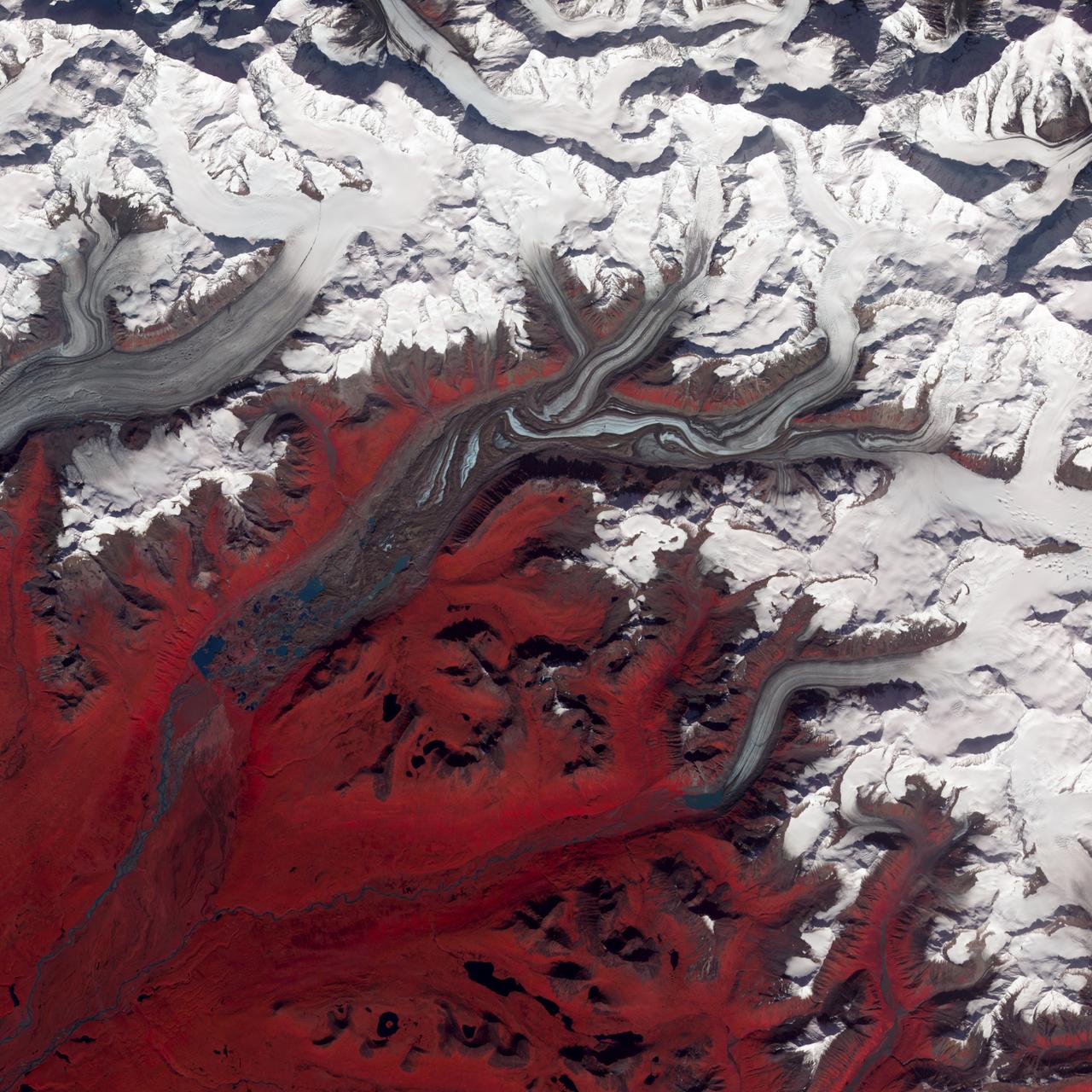

NASA image acquired August 27, 2009 Like rivers of liquid water, glaciers flow downhill, with tributaries joining to form larger rivers. But where water rushes, ice crawls. As a result, glaciers gather dust and dirt, and bear long-lasting evidence of past movements. Alaska’s Susitna Glacier revealed some of its long, grinding journey when the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA’s Terra satellite passed overhead on August 27, 2009. This satellite image combines infrared, red, and green wavelengths to form a false-color image. Vegetation is red and the glacier’s surface is marbled with dirt-free blue ice and dirt-coated brown ice. Infusions of relatively clean ice push in from tributaries in the north. The glacier surface appears especially complex near the center of the image, where a tributary has pushed the ice in the main glacier slightly southward. A photograph taken by researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (archived by the National Snow and Ice Data Center) shows an equally complicated Susitna Glacier in 1970, with dirt-free and dirt-encrusted surfaces forming stripes, curves, and U-turns. Susitna flows over a seismically active area. In fact, a 7.9-magnitude quake struck the region in November 2002, along a previously unknown fault. Geologists surmised that earthquakes had created the steep cliffs and slopes in the glacier surface, but in fact most of the jumble is the result of surges in tributary glaciers. Glacier surges—typically short-lived events where a glacier moves many times its normal rate—can occur when melt water accumulates at the base and lubricates the flow. This water may be supplied by meltwater lakes that accumulate on top of the glacier; some are visible in the lower left corner of this image. The underlying bedrock can also contribute to glacier surges, with soft, easily deformed rock leading to more frequent surges. NASA Earth Observatory image created by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using data provided courtesy of NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - ASTER Credit: <b><a href="http://www.earthobservatory.nasa.gov/" rel="nofollow"> NASA Earth Observatory</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Join us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b>