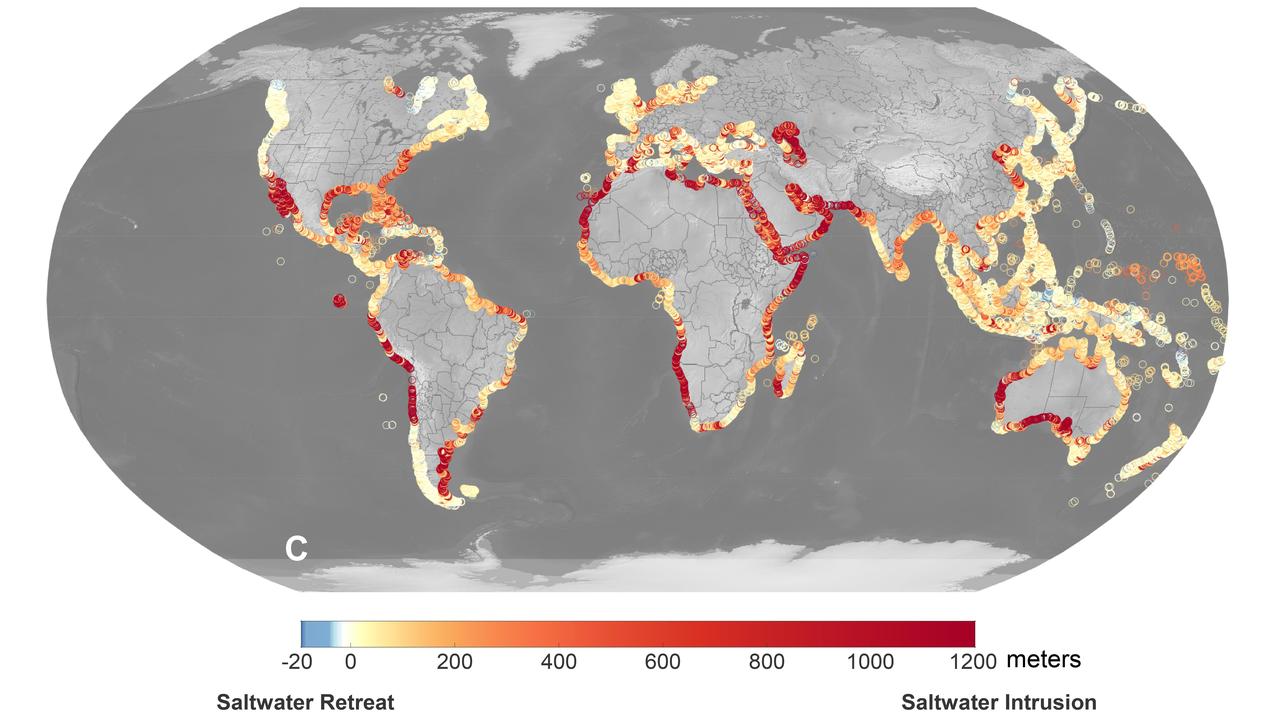

A recent study led by researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California that seawater will infiltrate underground fresh water supplies in about 77% of coastal watersheds around the world by the year 2100, as illustrated in this graphic. Called saltwater intrusion, the phenomenon will result from the combined effects of sea level rise and slower replenishment of groundwater supplies due to warmer, drier regional climates, according to the study, which was funded by NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense and published in Geophysical Research Letters in November 2024. In the graphic, areas that the study projected will experience the most severe saltwater intrusion are marked with red, while the few areas that will experience the opposite phenomenon, called saltwater retreat, are marked with blue. Saltwater intrusion happens deep below coastlines, where two masses of water naturally run up against each other. Rainfall on land replenishes, or recharges, fresh water in coastal aquifers (essentially, underground rock and dirt that hold water), which tends to flow underground toward the ocean. Meanwhile, seawater, backed by the pressure of the ocean, tends to push inland. Although there's some mixing in the transition zone where the two meet, the balance of opposing forces typically keeps the water fresh on one side and salty on the other. Spurred by melting ice sheets and glaciers, sea level rise is causing coastlines to migrate inland and increasing the force pushing underground salt water landward. At the same time, slower groundwater recharge resulting from reduced rainfall and warmer weather patterns is weakening the force behind the fresh water in some areas. Saltwater intrusion can render water in coastal aquifers undrinkable and useless for irrigation. It can also harm ecosystems and damage infrastructure. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26491

STS102-303-017 (8-21 March 2001)--- The STS-102 crew members used a 35mm camera on the flight deck of the Space Shuttle Discovery to record this image of the Aswan High Dam. The structure was completed in 1970 and is one of the largest earthen embankment dams in the world. It is 364 feet (111 meters) tall, 12,565 feet (3,830 meters) long and nearly 3,281 feet (1,000 meters) wide. When it was built the new reservoir required relocation of nearly 100,000 residents and some archaeological sites. Although the reservoir has benefited Egypt by providing power and controlling floods, according to NASA scientists, it has also had detrimental effects on the Nile system. Before the dam, an estimated 110 million tons of silt was deposited by the annual flood of the Nile, enriching agricultural lands and maintaining the land of the Nile delta. Now this sediment is trapped behind the dam, requiring artificial fertilization of agricultural lands and leading to erosion and saltwater intrusion where the Nile river meets the Mediterranean Sea.

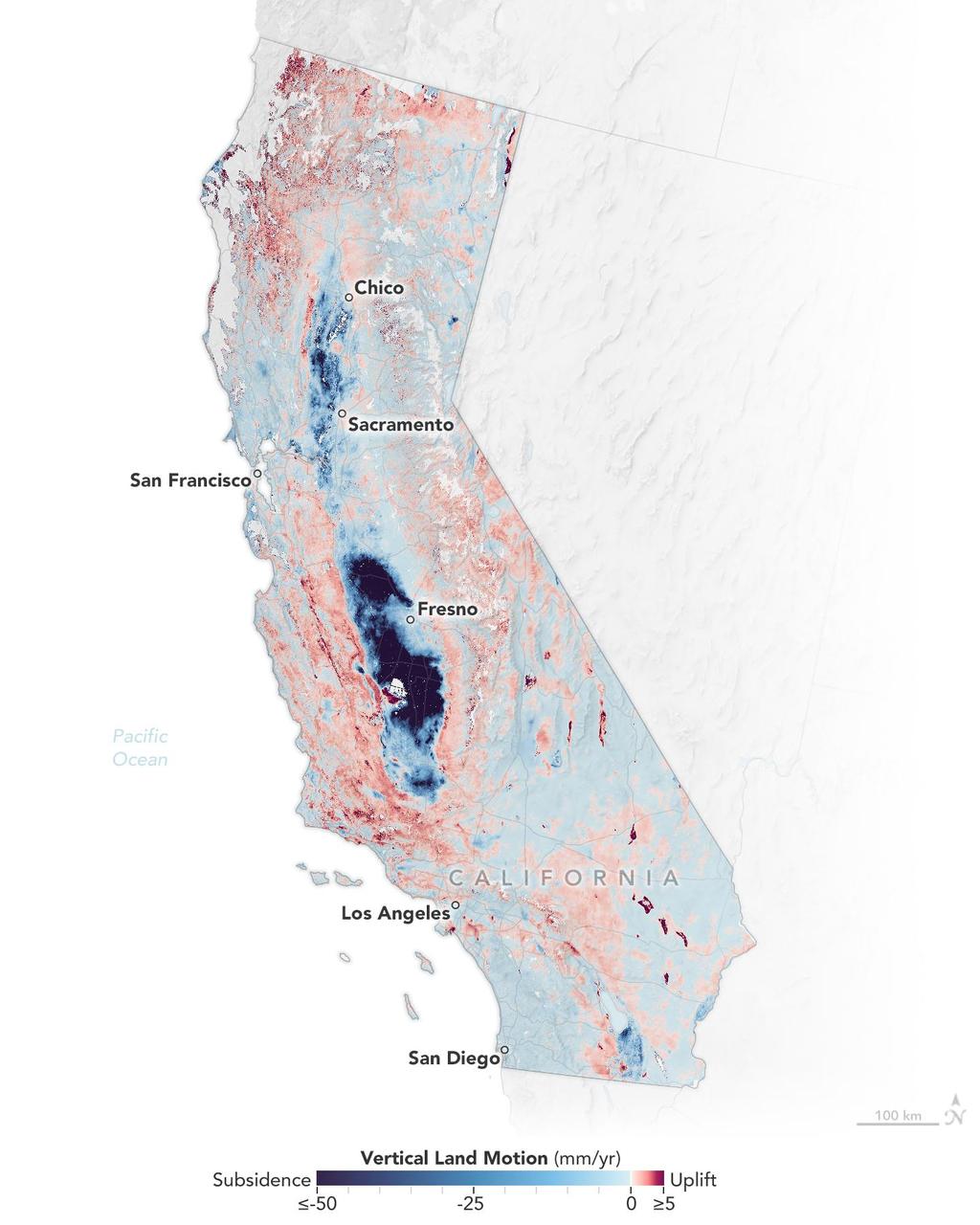

Researchers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) analyzed vertical land motion – also known as uplift and subsidence – along the California coast between 2015 and 2023. They detailed where land beneath major coastal cities, including parts of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego, is sinking (indicated in blue in this visualization of the data). Locations of uplift (shown in red) were also observed. Causes for the motion include human-driven activities such as groundwater withdrawal and wastewater injection as well as natural dynamics like tectonic activity. Understanding these local elevation changes can help communities adapt to rising sea levels in their area. The researchers pinpointed hot spots – including cities, beaches, and aquifers – at greater exposure to rising seas in coming decades. Sea level rise can exacerbate issues like nuisance flooding and saltwater intrusion. To gather the data, the researchers employed a remote sensing technique called interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR), which combines two or more 3D observations of the same region to reveal surface motion down to fractions of inches. They used the radars on the ESA (European Space Agency) Sentinel-1 satellites, as well as motion velocity data from ground-based receiving stations in the Global Navigation Satellite System. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25530

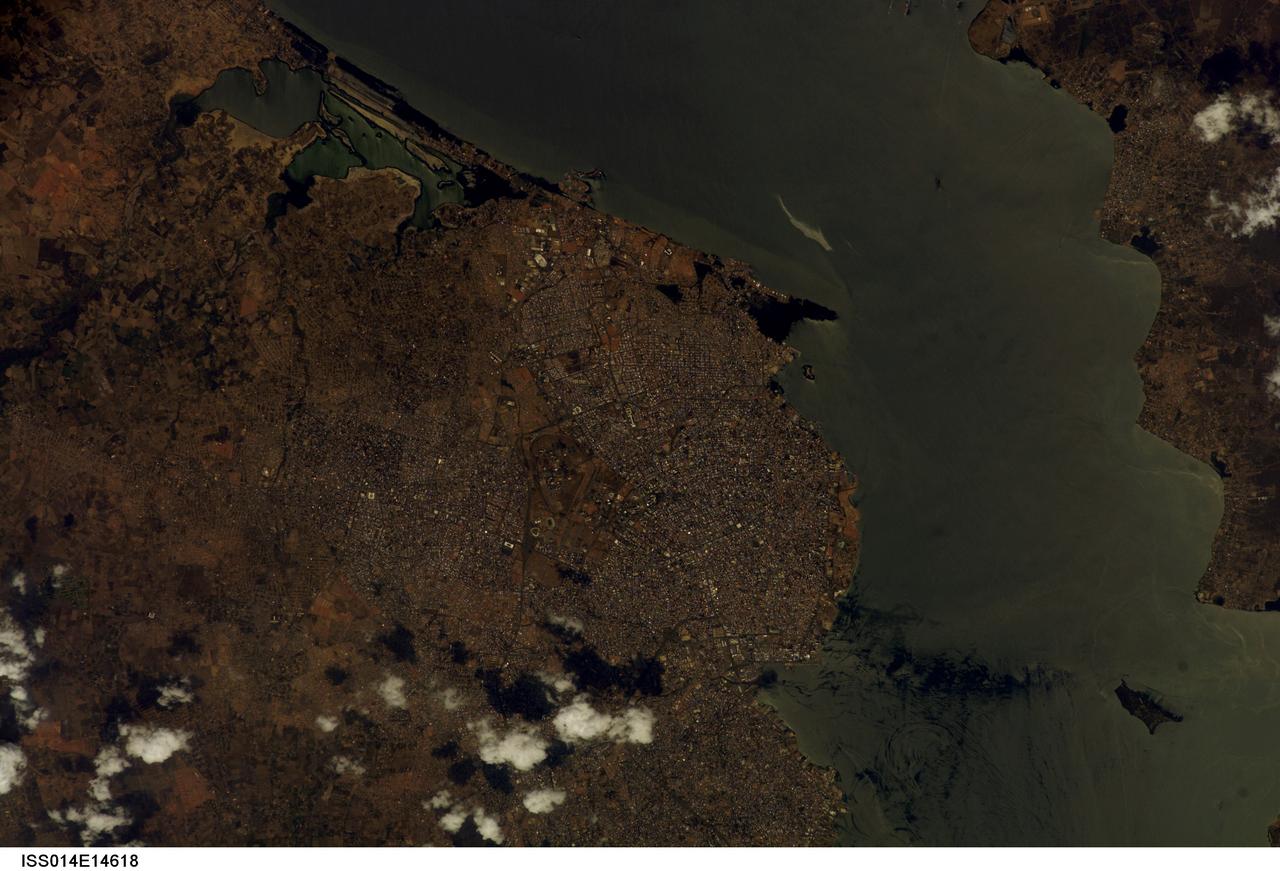

ISS014-E-14618 (23 Feb. 2007) --- Maracaibo City and Oil Slick, Venezuela are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 14 crewmember on the International Space Station. This view depicts the narrow (6 kilometers) strait between Lake Maracaibo to the south and the Gulf of Venezuela to the north. This brackish lake in northern Venezuela is the largest in South America. The lake and its small basin are situated atop a vast reservoir of buried oil deposits, first tapped in 1914. Venezuela is now the world's fifth largest oil producer. The narrow strait is deepened to allow access by ocean-going vessels, dozens of which now daily transport approximately 80 per cent of Venezuela's oil to world markets. Shipping is one of the main polluters of the lake, caused by the dumping of ballast and other waste. An oil slick, likely related to bilge pumping, can be seen as a bright streak northeast of El Triunfo. Other sources of pollution to the lake include underwater oil pipeline leakage, untreated municipal and industrial waste from coastal cities, and runoff of chemicals from surrounding farm land. Deepening the narrow channel for shipping has also allowed saltwater intrusion into the lake, leading to adverse effects to Lake Biota. Since the discovery of oil, cities like Maracaibo have sprung up along the northwestern coastline of the lake. With satellite cities such as San Luis and El Triunfo, greater Maracaibo has a population of approximately 2.5 million. Just outside the lower margin of the picture a major bridge spans the narrows pictured here, connecting cities such as Altagracia (top right) to Maracaibo.