Vital Signs: Taking the Pulse of Our Planet - Annual NASA reception and lecture hosted by the National Air and Space Museum and Sponsored by the Maryland Space Business Roundtable

NASA Administrator Charle Bolden, Dr. John Grunsfeld, Dr. Piers Sellers, Goddard Center Director Chris Scolese and MSBR president Ms. Yang hold a meet and greet with Wounded Warriors from Fort Belvoir, MSBR Final Frontier Students and STEM Partners from Summer of Innovation local camps at Vital Signs: Taking the Pulse of Our Planet - Annual NASA reception and lecture hosted by the National Air and Space Museum and Sponsored by the Maryland Space Business Roundtable

NASA Administrator Charle Bolden, Dr. John Grunsfeld, Dr. Piers Sellers, Goddard Center Director Chris Scolese and MSBR president Ms. Yang hold a meet and greet with Wounded Warriors from Fort Belvoir, MSBR Final Frontier Students and STEM Partners from Summer of Innovation local camps at Vital Signs: Taking the Pulse of Our Planet - Annual NASA reception and lecture hosted by the National Air and Space Museum and Sponsored by the Maryland Space Business Roundtable

NASA Administrator Charle Bolden, Dr. John Grunsfeld, Dr. Piers Sellers, Goddard Center Director Chris Scolese and MSBR president Ms. Yang hold a meet and greet with Wounded Warriors from Fort Belvoir, MSBR Final Frontier Students and STEM Partners from Summer of Innovation local camps at Vital Signs: Taking the Pulse of Our Planet - Annual NASA reception and lecture hosted by the National Air and Space Museum and Sponsored by the Maryland Space Business Roundtable

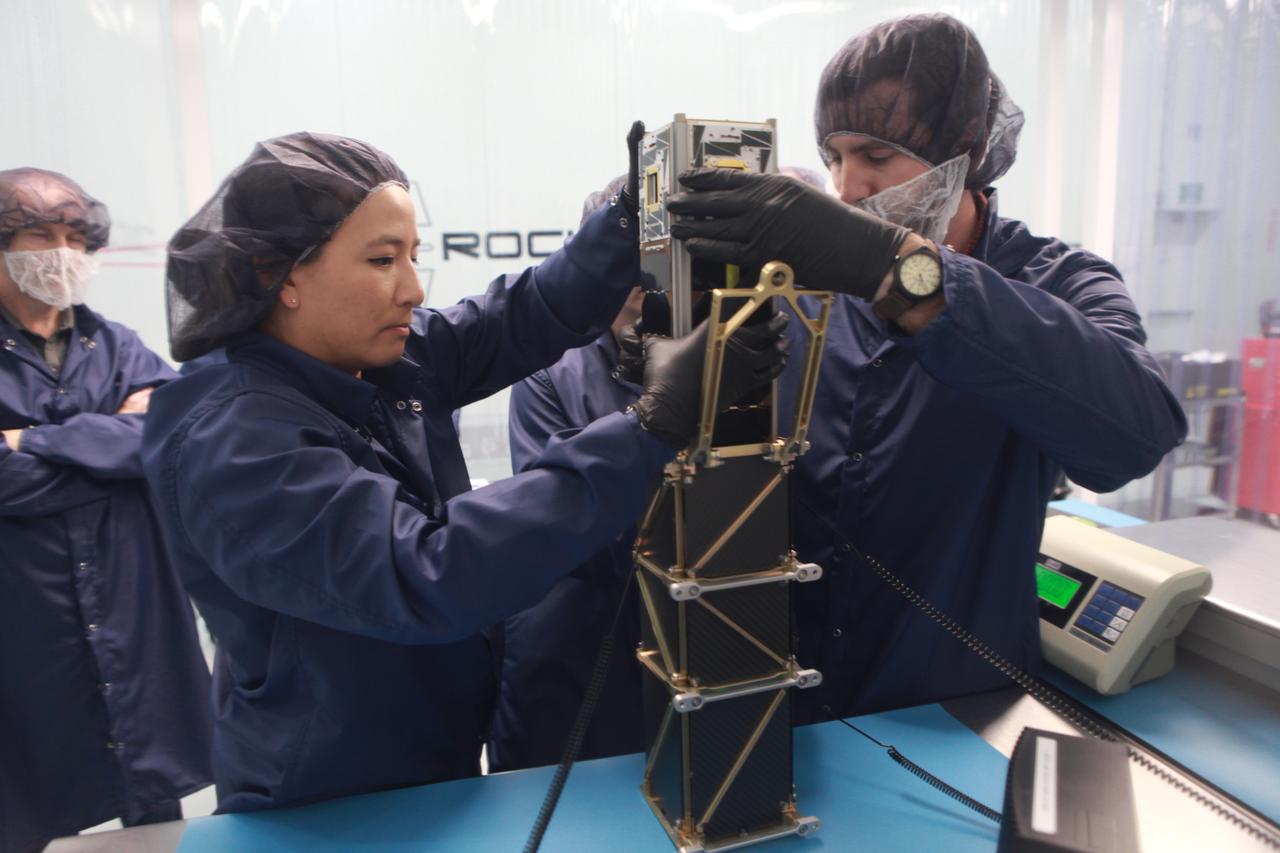

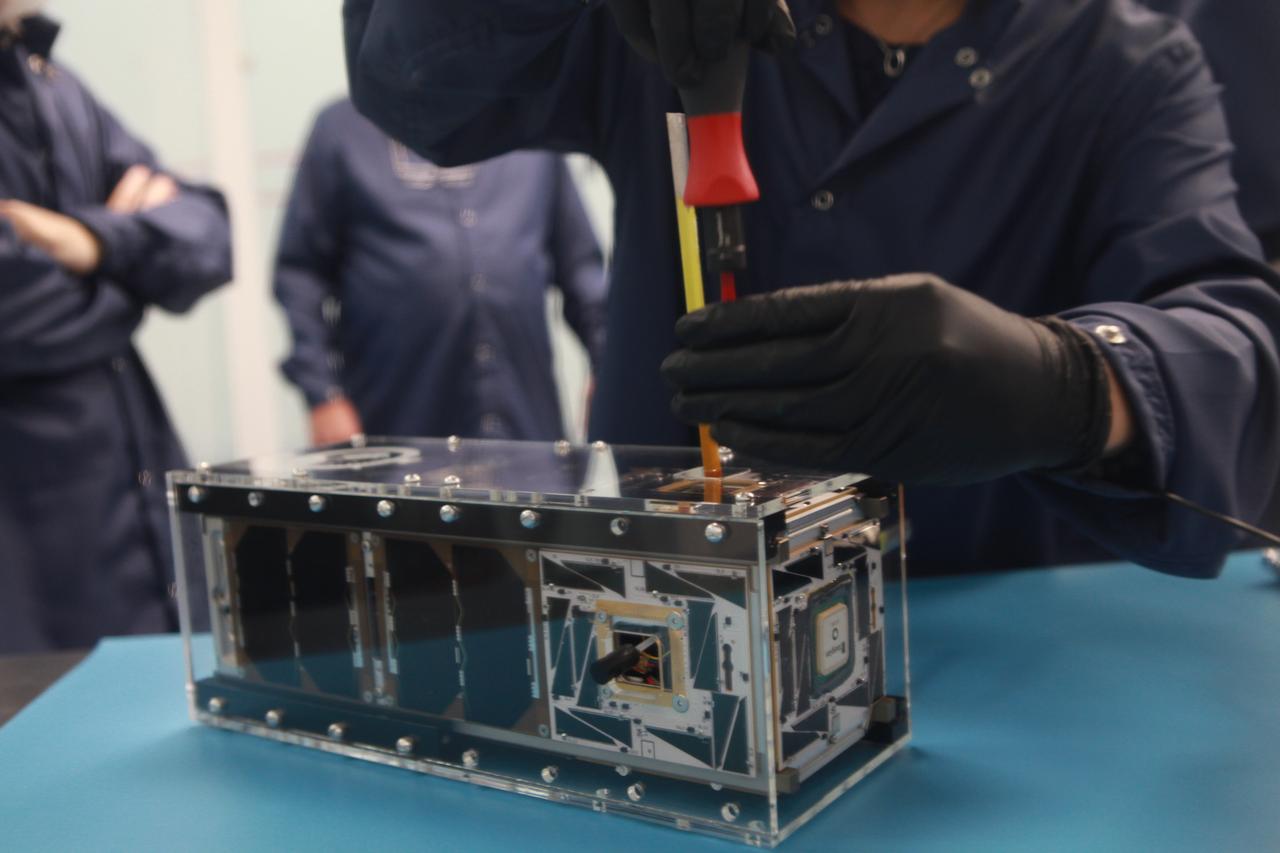

The goal of the CHOMPTT mission is to demonstrate new technologies that could be used for navigation and satellite networking in deep space. For future explorers and colonizers of the Moon or Mars, navigation systems like GPS here on Earth, will be essential. The key idea behind CHOMPTT is to use lasers to transfer time code data over long distances instead of radio waves. Because lasers can be more tightly beamed compared to radio waves, more of the transmitted energy reaches its intended target, making them more power-efficient. CHOMPTT takes advantage of this and of new miniature but very stable atomic clocks to produce a timing system with performance similar to that of GPS, but in a very compact and power efficient form factor. We will use a pulsed laser system, located at the Kennedy Space Center that will be synchronized with an atomic clock. Laser pulses will propagate from the ground to the orbiting CHOMPTT CubeSat and back. By precisely measuring the time of emission and detection of these pulses on the ground and in space we can calculate the time discrepancy between the ground atomic clock and the atomic clock on CHOMPTT. Our goal is to do this with an accuracy of 0.2 billionths of a second, or the time it takes light to travel just 6 centimeters. In the future, we envision using this technology on constellations or swarms of small satellites, for example orbiting the Moon, to equip them with precision navigation, networking, and ranging capabilities. CHOMPTT is a collaboration between the University of Florida and the NASA Ames Research Center. The CHOMPTT precision timing payload was designed and built by the Precision Space Systems Lab at the University of Florida, while the 3U CubeSat bus that has prior flight heritage, was provided by NASA Ames. The CHOMPTT mission has been funded by the Air Force Research Lab and by NASA.

The goal of the CHOMPTT mission is to demonstrate new technologies that could be used for navigation and satellite networking in deep space. For future explorers and colonizers of the Moon or Mars, navigation systems like GPS here on Earth, will be essential. The key idea behind CHOMPTT is to use lasers to transfer time code data over long distances instead of radio waves. Because lasers can be more tightly beamed compared to radio waves, more of the transmitted energy reaches its intended target, making them more power-efficient. CHOMPTT takes advantage of this and of new miniature but very stable atomic clocks to produce a timing system with performance similar to that of GPS, but in a very compact and power efficient form factor. We will use a pulsed laser system, located at the Kennedy Space Center that will be synchronized with an atomic clock. Laser pulses will propagate from the ground to the orbiting CHOMPTT CubeSat and back. By precisely measuring the time of emission and detection of these pulses on the ground and in space we can calculate the time discrepancy between the ground atomic clock and the atomic clock on CHOMPTT. Our goal is to do this with an accuracy of 0.2 billionths of a second, or the time it takes light to travel just 6 centimeters. In the future, we envision using this technology on constellations or swarms of small satellites, for example orbiting the Moon, to equip them with precision navigation, networking, and ranging capabilities. CHOMPTT is a collaboration between the University of Florida and the NASA Ames Research Center. The CHOMPTT precision timing payload was designed and built by the Precision Space Systems Lab at the University of Florida, while the 3U CubeSat bus that has prior flight heritage, was provided by NASA Ames. The CHOMPTT mission has been funded by the Air Force Research Lab and by NASA.

The goal of the CHOMPTT mission is to demonstrate new technologies that could be used for navigation and satellite networking in deep space. For future explorers and colonizers of the Moon or Mars, navigation systems like GPS here on Earth, will be essential. The key idea behind CHOMPTT is to use lasers to transfer time code data over long distances instead of radio waves. Because lasers can be more tightly beamed compared to radio waves, more of the transmitted energy reaches its intended target, making them more power-efficient. CHOMPTT takes advantage of this and of new miniature but very stable atomic clocks to produce a timing system with performance similar to that of GPS, but in a very compact and power efficient form factor. We will use a pulsed laser system, located at the Kennedy Space Center that will be synchronized with an atomic clock. Laser pulses will propagate from the ground to the orbiting CHOMPTT CubeSat and back. By precisely measuring the time of emission and detection of these pulses on the ground and in space we can calculate the time discrepancy between the ground atomic clock and the atomic clock on CHOMPTT. Our goal is to do this with an accuracy of 0.2 billionths of a second, or the time it takes light to travel just 6 centimeters. In the future, we envision using this technology on constellations or swarms of small satellites, for example orbiting the Moon, to equip them with precision navigation, networking, and ranging capabilities. CHOMPTT is a collaboration between the University of Florida and the NASA Ames Research Center. The CHOMPTT precision timing payload was designed and built by the Precision Space Systems Lab at the University of Florida, while the 3U CubeSat bus that has prior flight heritage, was provided by NASA Ames. The CHOMPTT mission has been funded by the Air Force Research Lab and by NASA.

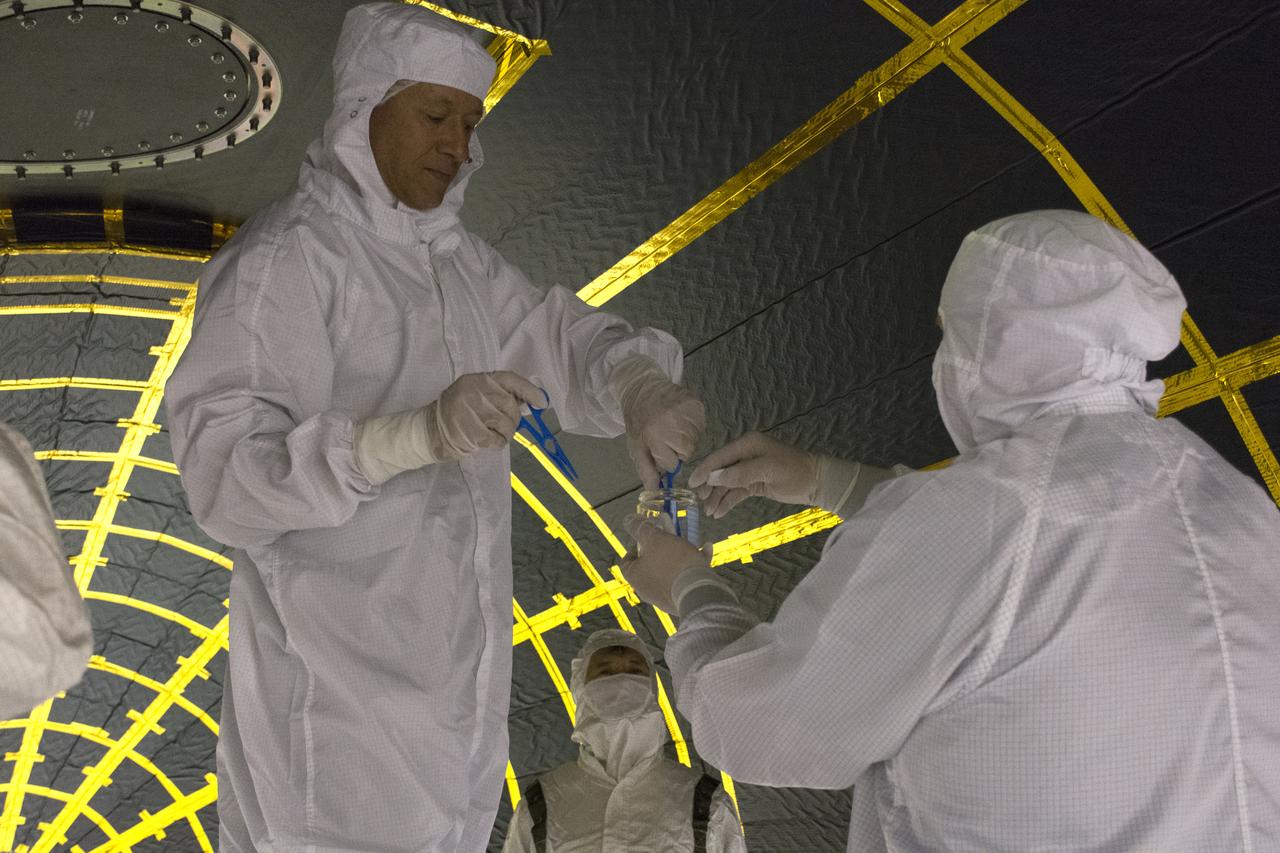

On Friday, April 6, 2018, in NASA’s Building 8337 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, technicians and engineers clean and take samples from the payload fairing the will protect NASA's Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2, or ICESat-2, satellite during launch. Liftoff atop a United Launch Alliance Delta II rocket is scheduled for Sept. 12, 2018, from Space Launch Complex-2 at Vandenberg. It will be the last for the venerable Delta II rocket. ICESat-2, which is being built and tested by Orbital ATK in Gilbert, Arizona, will carry a single instrument called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or ATLAS. The ATLAS instrument is being built and tested at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt Maryland. Once in orbit, the satellite is designed to measure the height of a changing Earth, one laser pulse at a time, 10,000 laser pulses a second. ICESat-2 will help scientists investigate why, and how much, Earth’s frozen and icy areas, called the cryosphere, are changing.

On Friday, April 6, 2018, in NASA’s Building 8337 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, technicians and engineers clean and take samples from the payload fairing the will protect NASA's Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2, or ICESat-2, satellite during launch. Liftoff atop a United Launch Alliance Delta II rocket is scheduled for Sept. 12, 2018, from Space Launch Complex-2 at Vandenberg. It will be the last for the venerable Delta II rocket. ICESat-2, which is being built and tested by Orbital ATK in Gilbert, Arizona, will carry a single instrument called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or ATLAS. The ATLAS instrument is being built and tested at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt Maryland. Once in orbit, the satellite is designed to measure the height of a changing Earth, one laser pulse at a time, 10,000 laser pulses a second. ICESat-2 will help scientists investigate why, and how much, Earth’s frozen and icy areas, called the cryosphere, are changing.

On Friday, April 6, 2018, in NASA’s Building 8337 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, technicians and engineers clean and take samples from the payload fairing the will protect NASA's Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2, or ICESat-2, satellite during launch. Liftoff atop a United Launch Alliance Delta II rocket is scheduled for Sept. 12, 2018, from Space Launch Complex-2 at Vandenberg. It will be the last for the venerable Delta II rocket. ICESat-2, which is being built and tested by Orbital ATK in Gilbert, Arizona, will carry a single instrument called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or ATLAS. The ATLAS instrument is being built and tested at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt Maryland. Once in orbit, the satellite is designed to measure the height of a changing Earth, one laser pulse at a time, 10,000 laser pulses a second. ICESat-2 will help scientists investigate why, and how much, Earth’s frozen and icy areas, called the cryosphere, are changing.

On Friday, April 6, 2018, in NASA’s Building 8337 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, a technician cleans and takes samples from the payload fairing the will protect NASA's Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2, or ICESat-2, satellite during launch. Liftoff atop a United Launch Alliance Delta II rocket is scheduled for Sept. 12, 2018, from Space Launch Complex-2 at Vandenberg. It will be the last for the venerable Delta II rocket. ICESat-2, which is being built and tested by Orbital ATK in Gilbert, Arizona, will carry a single instrument called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or ATLAS. The ATLAS instrument is being built and tested at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt Maryland. Once in orbit, the satellite is designed to measure the height of a changing Earth, one laser pulse at a time, 10,000 laser pulses a second. ICESat-2 will help scientists investigate why, and how much, Earth’s frozen and icy areas, called the cryosphere, are changing.

A group of Coast Guard seamen leave their ship to verify ice formations on the Great Lakes as part of an joint effort with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Lewis Research Center and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The regular winter freezing of large portions of the Great Lakes stalled the shipping industry. Lewis began working on two complementary systems to monitor the ice. The Side Looking Airborne Radar (SLAR) system used microwaves to measure the ice distribution and electromagnetic systems used noise modulation to determine the thickness of the ice. The images were then transferred via satellite to the Coast Guard station. The Coast Guard then transmitted the pertinent images by VHF to the ship captains to help them select the best route. The Great Lakes ice mapping devices were first tested on NASA aircraft during the winter of 1972 and 1973. The pulsed radar system was transferred to the Coast Guard’s C-130 aircraft for the 1975 and 1976 winter. The SLAR was installed in the rear cargo door, and the small S-band antenna was mounted to the underside of the aircraft. Coast Guard flights began in January 1975 at an altitude of 11,000 feet. Early in the program, teams of guardsmen and NASA researchers frequently set out in boats to take samples and measurements of the ice in order to verify the radar information.

jsc2022e062020 (6/30/2022) --- Space Health will create a digital twin of the astronaut from the data collected by the Bio-Monitor and demonstrate how this could be used for autonomous health monitoring on future space missions. (Image courtesy of CSA)